- January 2, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

The next week’s national news cycles likely will continue to beat to death the Trump-Biden election fiasco. But spare us, please.

Trump supporters hoped otherwise, but they knew the outcome all along. The Republican congressional establishment was only putting on a political show that it would attempt to do anything meaningful.

All of which leaves the majority of the 74 million Trump voters having to live like Hillary voters for the next four years — refusing to accept that Joe Biden won legitimately and trying to go about life anyway.

Just keep saying the “Serenity Prayer” …

“… Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can and the wisdom to know the difference …”

In that vein, we’re going to attempt here part two of Reinhold Niebuhr’s famous prayer — to try to have some effect on something that needs to change.

What we’re about to address is an issue that needs reforming in Florida. This same issue has festered and come before the Legislature almost every year for the past 25 years — and nothing has changed.

It’s not a major social issue like abortion or guns or health care for the poor. And it’s certainly not an issue that legislators like to take on because it’s not a political career maker. Here’s the other thing they don’t like: Every time they try to change the law, the press — specifically, newspapers — pillory the lawmakers for being against government transparency (and for good reason).

But this is an important issue. It affects every Floridian every day. Indeed, it goes to the heart of making sure state and local governments and all of their agencies operate openly and transparently. It goes to the heart of giving Floridians the ability to have a say in how their state and local governments operate. And in many instances it also goes to the heart of due process — protecting Floridians from having their properties unfairly and illegally confiscated.

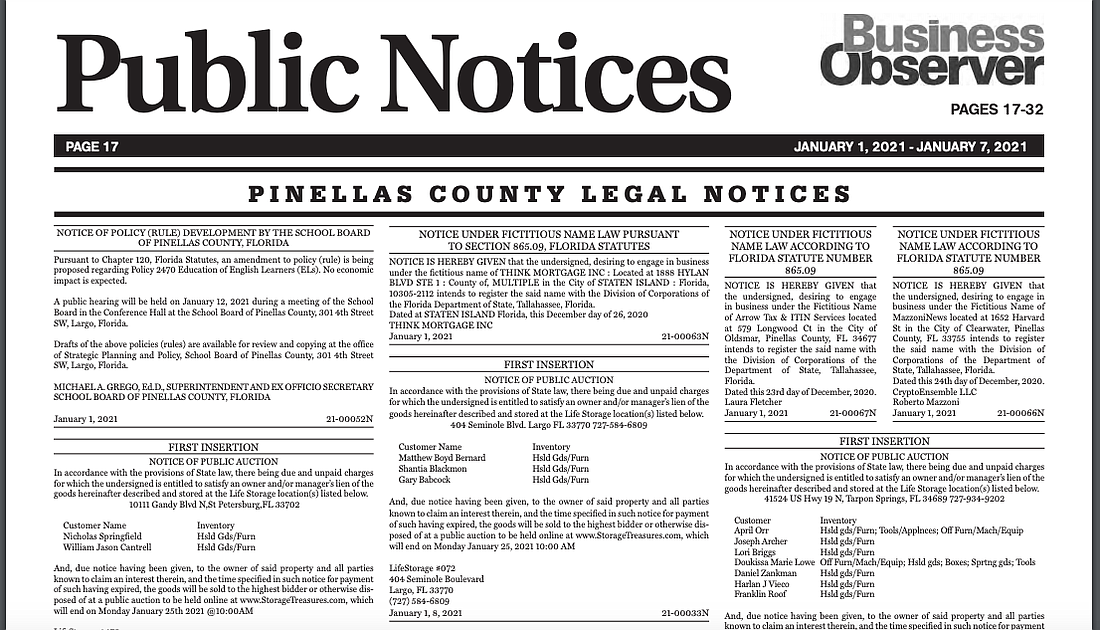

The issue: public notices.

As we said, it’s not sexy. What’s more, many lawmakers over the years are convinced Floridians pay little attention to them. And year after year one lawmaker after another makes the claim and complaint that public notices in newspapers and on their websites are simply a subsidy for newspapers and rip-off for taxpayers.

If they could have their way, they would shift public notices out of newspapers and onto government websites.

For many, this may sound like a good idea. But it’s not. It’s a bad idea.

We’ll show why and propose an alternative.

Meantime, taxpayers take note. This issue is coming up again when Florida lawmakers convene in March. Which means the time to address it is now. As we’ve learned over the years, almost all legislative deals are crafted behind the scenes before the session begins.

First, full disclosure: Our company and all of the paid-subscription newspapers in Florida generate revenues and profits from publishing government-mandated public notices. So it’s easy to conclude we — the Business Observer and Observer Media Group Inc. — have a vested interest in protecting the status quo.

But in fact, our company has been lobbying for more than a decade that the state’s public notice laws need reforming and updating. In part, we’ve been making the same argument lawmakers have made — that the Legislature decades ago crafted public notice laws in a way that gives daily newspapers and paid-subscription newspapers a protected monopoly on the publishing of public notices (and the revenues governments pay to have them published).

In fact, we’ve argued, and continue to do so, that the state’s daily newspapers are exactly what their editorials often criticize: They’re a special interest that uses the Legislature for special protectionism.

While lawmakers complain about the cost to taxpayers of publishing public notices, a portion of that cost is a direct result of the lack of competition they created to begin with.

At the risk of too much regulatory mumbo jumbo, here’s the deal: To qualify to publish most government public notices, newspapers, among other things, must publish five or more days a week. They also must have a periodical permit from the U.S. Postal Service, which requires more than 50% of the paper’s distribution to be paid subscribers.

That means free weekly newspapers are ineligible for public notices — that is, if the government body wants to meet its requirements for valid public notices. Many municipalities still publish notices in their communities’ free weeklies because they know the notices reach and are read by the taxpayers the cities and counties want to reach.

So here’s one of the conundrums of the statutes: The laws apply to a changed marketplace: Readership and circulation of free weeklies now surpasses the readership of paid dailies in many of Florida’s markets. What’s more, the cost to publish in free weeklies often is less than the cost to publish in the local paid daily.

Stand-alone websites are also prohibited from qualifying to publish public notices. The newspaper industry thwarted the threat of these potential competitors’ websites when it lobbied the Legislature to modify the statutes by requiring papers that publish public notices in print to post all notices on their websites as well — at no charge. The industry also created floridapublicnotices.com, a site that aggregates all notices from around the state — at no charge.

Those two steps made Florida’s public notice laws a national model. Indeed, to a large extent, you can argue Florida public notice laws are working — except for the lack of competition.

Here’s another barometer: Not once in a quarter-century has a consumer group or angry citizens lobbied lawmakers for changes in public notice laws. There is no public outcry for changing the state’s public notice laws.

The only groups that complain are local governments (e.g. the League of Cities and Florida Association of Counties) and one-off lawmakers who want revenge and retribution against their local newspaper for having published critical and/or unflattering reports about their behavior.

Local government bureaucrats complain primarily during recessions, when they must cut their budgets. They say they will save taxpayers millions of dollars by not having to publish notices in newspapers — if only they could post public notices on their own websites.

This is baloney. The cost of public notice advertising for most local governments is hardly noticeable in the scheme of annual spending. One example: Two years ago, when we measured public notice spending for Sarasota County, it amounted to 0.02% of a $1 billion budget — $267,000.

These government officials should be honest. The money is a cover for their real objections. Many of these officials don’t like spending money with they regard as an adversary and enemy. They think public notices are a nuisance, a time suck for staff. They believe their lives would be much easier if they handled public notices on their own websites. After all, isn’t that where the world is — online? Who reads newspapers? the argument goes.

Rep. Randy Fine, R-Palm Bay, agrees with all of this.

Fine is regarded as one of the Legislature’s Republican bulls and bullies. If he comes up with a legislative proposal, he cares little about anyone’s objections. He showed this last session when, seemingly out of nowhere, he proposed that New College of Florida, based in Sarasota, be merged with one of the other larger state universities. That totally surprised Sarasota-Bradenton lawmakers and the New College administration.

Two years ago, after the Florida Today newspaper published critical stories about Fine, he responded by filing a bill that no longer would require public notices to be published in newspapers. The law would allow them to be published on “publicly accessible websites,” e.g. government-operated websites.

The bill died. He proposed it again last year. It died again, unable to move in the Senate. He has proposed it again for 2021 — HB 35.

Last year, while speaking in committee on behalf of the bill, Fine told his colleagues: “The problem is the dramatic subsidy and cost that we’re putting on local governments by requiring them to buy these ads that people aren’t reading at vastly inflated prices. That is where the issue is.”

The issue is much more than that. There are multiple issues.

Let’s parse them and finish with a recommendation.

A dramatic subsidy?

Perhaps a more precise depiction would be a government-sanctioned monopoly. Lawmakers did this. They gave paid-subscription daily newspapers a monopoly. No one in his right mind today would consider starting a daily newspaper for the purpose of creating competition for public notices.

And if the dailies’ prices are too high, as Fine says, hello, that’s what happens when there is little competition.

A subsidy?

Fine and others seem to forget there is work involved handling and publishing public notices. Just as other private government vendors expect to be paid for their efforts, the same goes for newspapers. There is a cost to paper, printing and distribution.

Rep. Fine, like many other lawmakers, also argues it no longer makes sense that public notices have not migrated to online-only publishing in this age of digital information. It would be so much more efficient if government agencies were allowed to post public notices on their own websites.

This has multiple dangers.

Who trusts any government to be 100% honest and transparent? Who wants the government to be the sole disseminator of public information? What’s more, who trusts that information on the internet is authentic, reliable, trustworthy and verifiable?

That public notices flow through newspapers, a third party, is a safety mechanism for taxpayers. As part of their job with notices, newspapers are required to file sworn affidavits acknowledging the veracity and time of the notices and to archive notices in perpetuity in the event they are challenged. Governments can do that, too, but who trusts a fox in the hen house?

Here’s another serious flaw with governments publishing notices online: Few people would see them, negating two of the purposes of public notices — visibility and accessibility.

For instance, whom do you know would spend the time every day or weekly searching government websites specifically for public notices of tax increases, zoning changes, water-use permits, deaths of creditors, upcoming public meetings and dozens of other government actions that affect taxpayers?

One of the positives of still having notices in print is the serendipitous nature of them. When a reader pages through his local paper, he discovers unexpected news and information. Likewise with public notices. Newspapers push out notices to the public. Online, they sit in darkness until someone seeks them out; that’s not public notice.

The result of online-only notices: less government transparency than what exists now.

Altogether, here is the paradox of what Rep. Fine and other Republican lawmakers want when they say government agencies should publish online public notices: They are hypocrites.

Republicans tout themselves as the advocates and champions of smaller government; government transparency and accountability; and, private enterprise and market competition.

But almost everything they are proposing with public notices will achieve the opposite: bigger government; more government cost; more government control and power over public information; less transparency for the public; and less private enterprise and fewer private jobs.

Florida’s public notice laws need reforming, to be sure. They need to be adjusted to the times. But that doesn’t mean simply shifting them all online — for the reasons cited above.

Indeed, daily print newspapers may be declining in readership, but free weekly newspapers are thriving, and both still are relevant and a valid source for public notice because of the serendipity described above; accessibility in print and online; and the veracity and verifiability.

In our libertarian world, we would let the marketplace decide how to operate public notices. Let the purveyors of public notices (governments, agencies, lawyers, banks, storage centers, etc.) decide which media make the most sense to disseminate their public notices — newspapers, TV stations, websites, radio — for effective public notice. And let private businesses that want to publish the notices compete. They would do so on the basis of meeting their customers’ needs, e.g. effectiveness, transparency, cost, accessibility, reliability and verifiability.

We know that scenario is unlikely. The daily newspapers will oppose such a free-market system to their deaths. And lawmakers won’t give up their power to regulate.

By the same token, to adopt Rep. Fine’s legislation (or an even worse proposal in Senate Bill 402) would ignore and disregard what is really needed.

Public notices — the act of keeping citizens and taxpayers informed of their governments’ activities — are not life and death. But they are essential and necessary for a proper functioning democratic republic. As such, they deserve serious deliberation.

These are the questions that should be examined and explored: In this age of digital information, what would be the most effective form of delivering efferctive public notices? What would be the best, most effective way to serve the taxpayers’ needs?

We would urge Florida’s lawmakers to be thoughtful and smart. Answer those questions before changing anything.