- December 22, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Vacation resort owner Garrett Kenny believed so much in 2020, what he thought was going to be “a very very good year,” he broke ground on a $3.5 million events and wedding center in 2019. On the grounds of Balmoral Resort in Polk County, the facility was going to complement some other new projects there, including a $5 million sports facility that opened last year.

Through January, 97% of the rooms at Balmoral were booked in March, worth some $1 million in business. Roughly 80% of April was spoken for. But by the second week of April, Kenny says his company, Haines City-based Feltrim Group, which did $32.6 million in revenue in 2019, was “on life-support,” from the impact of the coronavirus pandemic. Cancellations boomed. Future bookings cratered. In the hospitality business for 40 years, Kenny trimmed Feltrim’s payroll from 70 to five people.

‘I’m going to keep my head up. I’m not going to quit. But this world is going to be a much different place when this is over.’ Garrett Kenny, Feltrim Group

Kenny’s experience with the catastrophic collapse of business isn’t necessarily unique — thousands of Florida companies are seeing a wide range of losses, with few spared in the pandemic’s long reach. Kenny, likewise, joined a big group of business owners in seeking some type of financial relief from the litany of state and federal loan programs. His experience there — one part joy, one part hurry up and wait — shows that, anecdotally, at least, the floodgate of money isn’t a total fix. (Feltrim missed out on $300,000 in the first round of the federal Paycheck Protection Program, but it did get $150,000 in two loans from the state’s $50 million emergency bridge loans fund.)

In multiple interviews with business owners and bankers across the region about the bevy of aid and loan programs, particularly PPP, a few other themes emerged. A big one: confusion reigns. That includes how a company qualifies for the funds; when it gets said funds; and, most notably, why there was such variation in how banks handled the applications. The $350 billion dried up April 16, which leaves tens of thousands of business waiting. The second round of funding — after a week of political haggling in Washington, D.C. — totals $310 billion.

“Now that many more banks will know what they are doing, money should reach businesses fairly fast,” says Brooke Mirenda, president and CEO of the Sunshine State Economic Development Corp., a Clearwater-based nonprofit lender that specializes in SBA 504 loans.

A former banker with BankUnited and Florida Capital Bank, among other lenders, Mirenda crystallizes the top complaint many bankers and business owners have about the loan programs: uncertainty. “There have been so many changes,” Mirenda says. “It seems like it changes every other day.”

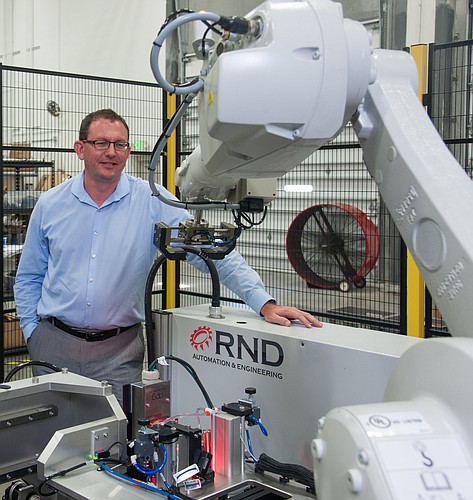

Uncertainty — combined with a dose of anger directed toward his bank — initially crippled Sean Dotson, CEO of Lakewood Ranch-based RND Automation, which engineers, designs and manufacturers robotic, packaging and assembly automation equipment. RND has 46 employees and did $12.38 million in revenue in 2019, up 76.85% from $7 million in 2018. “We had several orders ready to hit,” Dotson says of the company’s pre-pandemic status, “then some of them got pulled.”

Dotson applied for several loans, including PPP and an Economic Injury Disaster Loan. He says Florida’s emergency bridge loan program, in which Garret Kenny’s Feltrim and 950 or so other businesses received a cumulative $50 million, was too cumbersome to even bother. “This is like having to make a blind decision without all the facts,” Dotson says in April 21 interview, before the second round of PPP money was approved. “It’s ridiculously frustrating.”

‘I told our banker, who I like, that ‘your bank screwed up.’ They had no idea what they were doing, in my mind, and that might have cost 46 people their jobs.’ Sean Dotson, RND Automation

But Dotson’s real ire was saved for his bank: Chase. He’s been banking there for at least six years, he says, including lines of credit and business deposits. “Chase, our bank, has been awesome for many years,” Dotson wrote in a April 17 LinkedIn post. “Until today.”

Dotson applied for the PPP loan, seeking nearly $1 million. He filled out Chase’s online application and was told he was in the queue. Days passed, and despite repeated calls, the money dried up before he got the loan. “I told our banker, who I like, that ‘your bank screwed up,’” Dotson says. “They had no idea what they were doing, in my mind, and that might have cost 46 people their jobs.”

One silver lining: On April 20 Dotson, now working with ServisFirst Bank, applied for the second round of PPP loans. As of April 22, he was told by bankers there he was approved for funding — once round two is open.

In his LinkedIn Post, Dotson counters some national PPP headlines, where the focus has been on the multiple big businesses and publicly traded companies that got multimillion-dollar interest-free loans. That list includes 15 companies with a market cap of over $100 million. But Dotson, in talking with other business owners and assessing his own situation, says he thinks Chase and other big banks chose smaller amounts “to limit their exposure.”

Data backs up that theory, that the bulk of the funds of the first round of PPP loans went to small businesses — despite the outliers and national media coverage. The overall average loan size was $206,000, according to SBA documents. Also, 74% of all loans were under $150,000, and 87.5% were under $350,000. Out of the 1.66 million in total loans under PPP, 0.27% exceeded $5 million, the data shows.

Although Dotson’s experience was sour, Sarah Laroque, president and CEO of North Port-based ecosystem restoration firm EarthBalance, reports the opposite. Working with BBVA’s Southwest Florida office, and its market president Nick Roberts and others, Laroque says, was a breeze. Her company, with four offices statewide, about 100 employees and some $15 million a year in revenue, does mitigation land banking, environmental consulting and related services.

The bulk of EarthBalance’s clients are municipalities. That gives the company a cushion until June, when the fiscal year usually flips for governments. That cushion is also Laroque’s biggest anxiety — worrying that the third and fourth quarters will be brutal. “We are on the edge of our seats,” waiting to see how deep government cuts will be, she says. “I’m not sure killing weeds in the woods will be a top priority.”

That’s why she appreciates the flexibility of the PPP loan. And also why she appreciates Roberts and his team. “I want to keep all our employees’ families fed,” Laroque says. “I feel very fortunate BBVA worked so hard to get us the full amount.”

Examples like what Dotson and Laroque experienced leave both an opening and affirmation for one the sectors that’s thrived amid the coronavirus chaos: community banks.

Community banks in the region handled thousands of PPP loans worth billions of dollars, with many bankers logging weekends and nights to get applications moving. That was the case at Gulfside Bank — the newest bank in the region, having opened in late 2018. Gulfside President and CEO Dennis Murphy says he and the team worked 15 days in a row, only taking a break for Easter Sunday. The bank handled 70 loans worth $13.5 million — normally three months of work crammed into two weeks, Murphy says.

A series of PPP loans Gulfside worked on was for the Sarasota area restaurants run by the Caragiulo family, including Caragiulos. Co-Owner Paul Caragiulo cites the efficiency and, above all else, direct and quick communication with Gulfside as a key to staying sane when awaiting PPP information. The company ultimately received PPP loans for all four locations. “They did everything they said they would do,” he says.

The 2020 chairman of the Greater Sarasota Chamber of Commerce, Caragiulo adds that in his conversations with business owners, the banking theme holds: Community banks came through for the most part while big banks not so much. “It’s really become an advantage to be a small market community bank,” he says.

On that theme, at least 15 of the 70 PPP loans at Gulfside, Murphy says, were new clients. Also, the bank’s work led to a pipeline of nearly 20 new clients seeking about $4.2 million in PPP loans for round two “We’ve heard from a lot of clients who weren’t happy with the experience at some of the larger regional and national banks,” Murphy says. “But at times like these you have to step up. This is why you do it. You want to be able to help people through good times and bad times.”

While Murphy and other bankers prepare their banks for more PPP work, executives, like Dotson, Laroque and Kenny, the Polk County resort owner, prepare for a new, post-pandemic world.

“I’m going to keep my head up,” Kenny says. “I’m not going to quit. But this world is going to be a much different place when this is over.”

(This story was updated to reflect the correct restaurants owned by the Caragiulo family.)