- April 5, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Within the past two years, both the New York Post and Los Angeles Times have reported on the comeback of — wait for it — the fanny pack. With esteemed publications on both coasts covering the phenomenon, surely it can’t be fake news.

So if the fanny pack is back, can the briefcase be far behind?

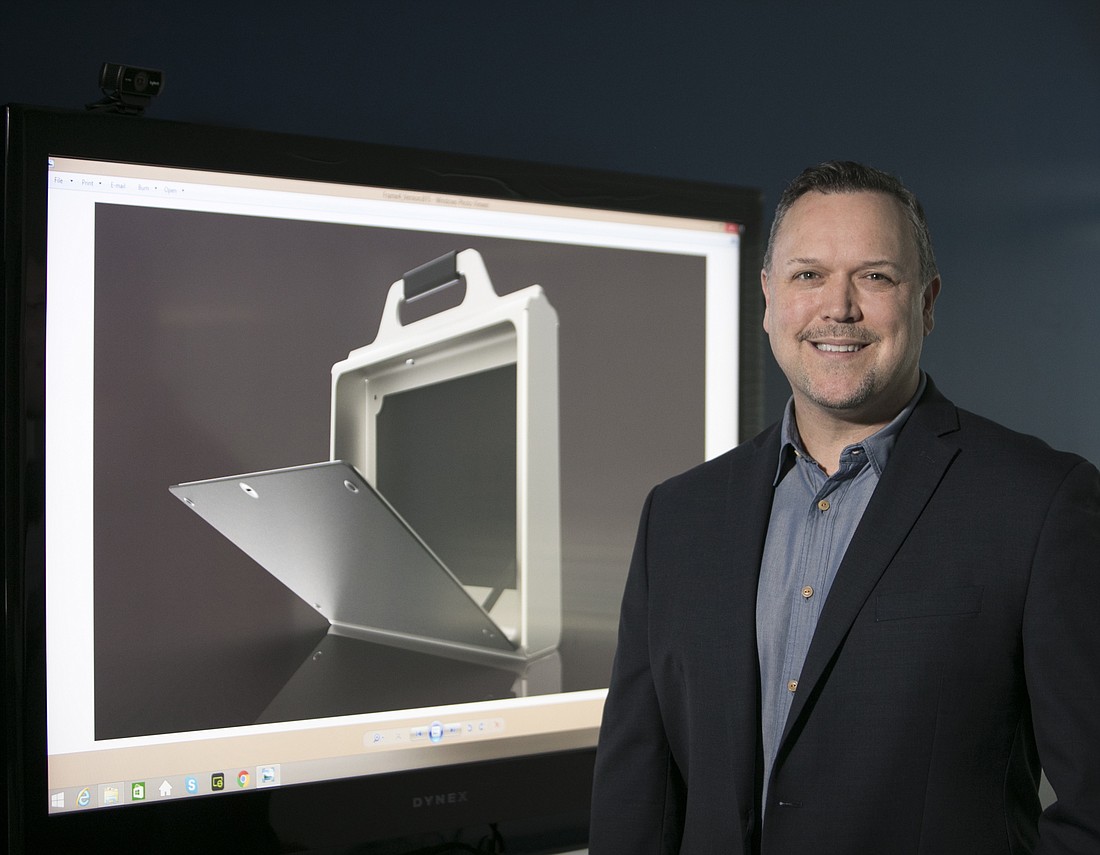

Eric Polins, a managing partner at HCP Associates, a Tampa marketing and communications firm, believes the answer is yes. So much so that he has put $20,000 of his own money on it and earned a U.S. patent for his Better Briefcase design.

“It's not the old briefcase that attorneys would carry around all their files in,” Polins says. “It's more of a wallet for your smartphone, your keys, a cup, maybe a laptop.”

“I just want to make something that will go out into the world that would be for everybody and not just old guys.” Eric Polins, managing principal at HCP Associates in Tampa

With interchangeable panels that can change the entire look of the briefcase in mere seconds, the Better Briefcase is akin to a Swatch Watch (millennials, Google that reference) for office workers.

“You could have snake skin on one side and a solar panel on the other,” Polins says. “That’s another thing I’m working on: photovoltaic panels that could charge whatever’s inside [the briefcase].”

Polins estimates that he has already spent four years developing the briefcase. The patent application process took two years. He’s put in hard work, for sure, but now, without even having a prototype ready, he faces the task of finding a manufacturer and distributor, as well as developing a marketing strategy for the product.

His plan, based partially on career experience of taking ego out of the equation and focusing on an end goal? “Don’t be greedy,” he says.

Polins, a former filmmaker and father of two young children, says he has no desire, at age 50, to give up his day job to chase an entrepreneurial dream. “I’d like to get a license in perpetuity,” he says. “Right now, it’s just me; I own 100%. If that goes down to 5%, it’s 5%. I’ll have another idea. That’s the key: Don’t be greedy. I just want to make something that will go out into the world that would be for everybody and not just old guys.”

The Better Briefcase, he says, “is all about individuality and celebrating your individuality” — themes that have been shown to resonate with millennial consumers. “We can give millennials a briefcase version of the Swatch that we got in the 1990s.”

Polins says the product will also boast generational crossover appeal because of its versatility. He has drawn up plans for a version with straps that could be worn over the shoulder or on the back, like a backpack. He wants to keep the cost reasonable — under $300, ideally — with versions at different price points, depending on the quality of material, such as recycled plastic, carbon fiber, metal or even bamboo.

“I just want somebody to take the concept, the housing and brand it,” he says, adding that he’s even willing to give up the “Better Briefcase” brand name. Age and experience, he says, have taught him to work on creative projects with a certain degree of detachment.

“When I was younger, especially with movies, I always made the mistake of, whenever I would write a script, believing in it too much,” he says. “My judgment was clouded by how popular I thought it would have been. As an inventor, you have to look at [your product], be honest and say, ‘Is this something that is worth my time?’ I had to think about that.”

Polins’ St. Petersburg-based patent attorney, Brittany Maxey, believes the briefcase will be a hit with a wide range of customers. The list ranges from artists, musicians and other creative professionals to lawyers like her who need to transport documents that won’t fit in a purse but don’t want to lug around a suitcase on wheels or wear a backpack like a college student.

“Women, especially, don’t want to have a boring old briefcase,” Maxey says. “Briefcases are expensive and, being a female, the briefcase choices that are out there are just not very appealing. And the ones that are — they’re just too small.”

Maxey says it’s vital inventors work with their attorneys early in the patent application process to anticipate questions U.S. Patent Office examiners — most of whom are scientists and engineers — might have. “We did that research and only got one office action,” she says, referring to patent examiners’ queries about the uniqueness of an invention. “It’s an iterative process back and forth with the government. To get a patent, [an invention] has to be new, useful and not obvious.”