- April 14, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

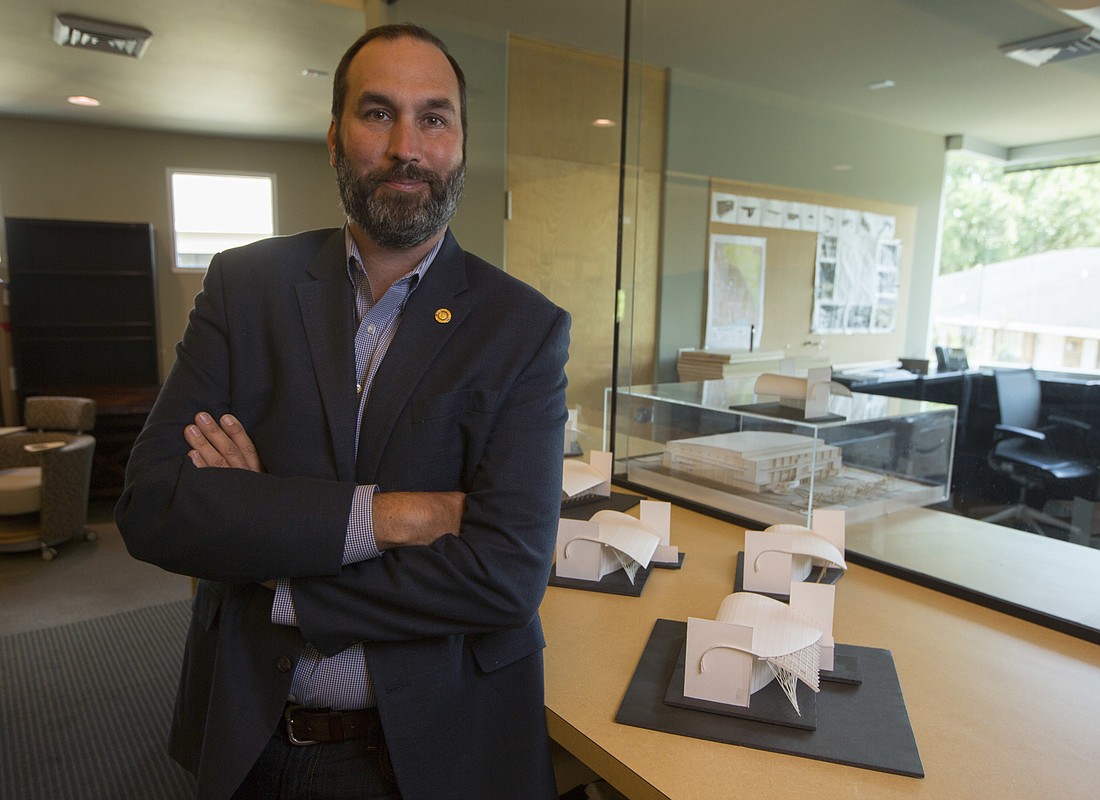

More plus more, in expertise and sectors, is the linchpin that launched a recent merger of two of the largest Polk County architectural and design firms. Yet the tie-up, of WMB-ROI and The Lunz Group, says one of the executives in the deal, was more shotgun marriage than long courtship.

The results, believe both companies, are wedded bliss: Operating under The Lunz Group, the 40-plus employee firm now has five offices — Dunedin/Clearwater, Lakeland, Winter Haven, Celebration and Melbourne — spanning Central Florida’s Interstate 4 corridor from Pinellas to Brevard County. The Lunz Group did $4.7 million in revenue in 2018, up 17.5% from $4 million in 2017. Both firms were based in Lakeland prior to the deal, of which financial terms weren’t disclosed.

“It’s no accident we have offices on both ends of the I-4 corridor with Lakeland in the middle,” says WMB-ROI CEO Steven Boyington. “We see growth along the I-4 corridor as one reason to merge.”

Adds Boyington: “We’re not trying to build a firm. We’re trying to pass on relationships” each has curried over decades. “We’re not after jobs. We’re after clients and want to build those relationships.”

WMB-ROI, founded in 1980, specializes in multifamily, assisted living and medical/health care construction. Its portfolio includes West Lake Village, Florida Southern College’s Christoverson Humanities Building, Legoland Florida Beach Retreat and the Lakeland Yacht and Country Club.

'We’re not-Tampa-based, not Orlando-based, we’re I-4 based, from Clearwater to Melbourne.' Brad Lunz, The Lunz Group

The Lunz Group, established in 1987, has expertise in medical, government and transportation/logistics. Among its projects are NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center, Watson clinics, the Auburndale Community Center and two Saint Leo University student-housing buildings.

With different emphases in varied sectors, the two were not head-to-head rivals and, says Lunz Group President Brad Lunz, shared “30 years of strong mutual respect for each other.”

Even so, it took what Boyington calls a “shotgun wedding,” when the Lakeland Economic Development Council coerced the firms to work together on the 38,000-square-foot Catapult 3.0 project in 2017, to see beyond competition. While working with Lunz on Catapult, Boyington says he “saw a glimpse of what we could accomplish when we work together and the added value we could bring to our clients.”

Lunz was equally impressed with what WMB-ROI brought to the project. He too realized if the firms combined their expertise, they could offer more services across more sectors. “How does this better our teams? That was the guiding force,” Lunz says

Ultimately, he determined a merger would be a “one plus one equals five deal.”

The merger was announced in early March. Lunz says the muscled-up firm can deliver the same services urban architectural companies can, but tailored for “communities that need the resources of a regional firm.”

“Development and growth are not just happening in urban centers,” he says. “We’re not-Tampa-based, not Orlando-based, we’re I-4 based, from Clearwater to Melbourne, and have the capacity to provide expertise in our hometowns. With our new size and capacity, our clients have a local option for any scale of project.”

A merger presents integration and other challenges. But Lunz can lean on lessons learned in 2016, when Lunz Prebor Fowler acquired Dunedin’s Graham Design Associates to become The Lunz Group. The key, he says, is leadership among merging firms must know and trust each other, understand who they are and their market.

Lunz’s father, Edward Lunz, who founded Lunz Prebor Fowler 32 years ago, has known Boyington for almost 40 years. The elder Lunz remains active in the firm but seeks to cut back. So Boyington, 61, “represents a nice ladder in between” him, at 44-years-old, and his father, Lunz says.

“This merger puts us in a strong position for sustainable growth,” says Lunz, “allowing us to foster leadership within our company.”

Another challenge in the merger, industry specific, is architects, engineers and planners can bend egotistical and be somewhat non-conforming. That hasn’t been an issue yet, Lunz and Boyington report. “I was asked that question today. ‘How did you manage the egos?’” Lunz laughed. “Well, we didn’t have egos against each other.”

“Our ego,” Boyington adds, “is founded on service to community and to business.”

The keep-the-ego in check mantra even applies to Lunz, who says with Boyington’s counsel, it’ll be less likely he’ll commit the “No. 1” mistake by any professional service business: “Not listening to the client.”