- November 23, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

It all started in Paris.

The 2015 City of Light attacks involved terrorists at multiple locations using assault weapons and explosives to harm civilians. Watching news footage of the attacks, Barry Gorski had an idea.

He wanted to help develop a product that could quickly test for the presence of explosives made with peroxide, an ingredient in some homemade bombs. Gorski shared his thoughts with Chris Baden, a Bradenton resident whom he had worked with on past entrepreneurial projects involving vehicle-mounted power and security technology.

Baden was intrigued. The pair, along with Baden's father, Ray Baden, formed a research company, Myakka Research Group, to pursue the product. At the beginning of 2017, Chris Baden says the company, Trace Eye-D, was formed for the specific purpose of bringing the products they are developing to market.

A year later, the company has made progress — despite several obstacles.

The products — named PB-33, for peroxide-based, and NB-36, for nitrogen-based — are similar to wet wipes passed out at restaurants with messy food. The patch inside turns purple on the spot when it comes into contact with explosive threats from peroxide-based trace residue. Baden says it provides a “simple, fast color metric to detect explosive residue.”

Trace Eye-D, for most of 2017, has worked with the Transportation Security Administration and the Department of Homeland Security to conduct field trials at major airports observed by TSA agents. Through testing, Baden says the company has solid data supporting that the product is nearly 100% reliable. Baden describes the testing the company is performing as a “long and arduous road that not every startup goes down.”

Research and development, along with testing processes, are notorious for being costly for tech startups — all the more so in high-tech security. While Baden declines to disclose how much he and his father have invested in Trace Eye-D, he says it's fair to say, “the Badens have gone all in.”

To date, the company has not sold any products, but hopes to have trials out within three months and products for sale by the end of the second quarter.

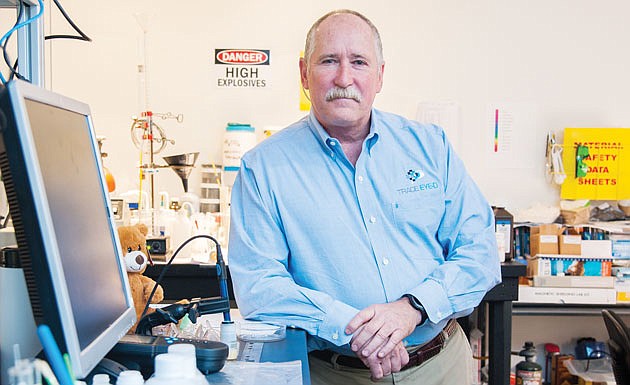

Gorski, a former Marine who served in Vietnam and has experience in explosives, is the director of research and development for Trace Eye-D, which has a research facility in Sarasota and a company headquarters in Bradenton.

Inside the research facility, the conference room is full of posters of ingredients that can be combined to build homemade explosives. They are sobering images of common household items that can be found at drugstores, hardware sores and grocery stores.

The facility also has a lab where employees work on developing the company's products, including one for detecting threats of peroxide-based explosives. Baden says the company filed a patent for the product over a year ago, but isn't sure yet when the patent will come through.

The company has received help along the way through interns from State College of Florida in Bradenton, where chemistry, biology and engineering students work in Trace Eye-D's research and development unit. In fall 2017, 10 students were involved in the program. This spring, 11 are involved. The students helped design a testing protocol the company can use for its products.

Jose Ors, the Natural Science department at SCF who runs the program with Trace Eye-D, says students continue to work with Gorski in product development. “From the college perspective,” he says, “it's a really good use of the relationship with the community.”

Meanwhile, in seeking multiple revenue sources, Trace Eye-D is working on a formula to detect nitrate-based explosives. Baden says the plan is to have that on the market in 2018. The firm also plans to develop drone technology that could be used for threat detection. With all of its products, Baden says, “There's a global demand for this.”

Clients for Trace Eye-D's products could come from many realms, including the military, law enforcement and security providers. They could be used at a variety of locations — airports, stadiums, concert venues, borders and ports — to detect explosive risks. Baden says, “We know the need is out there.”