- January 2, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

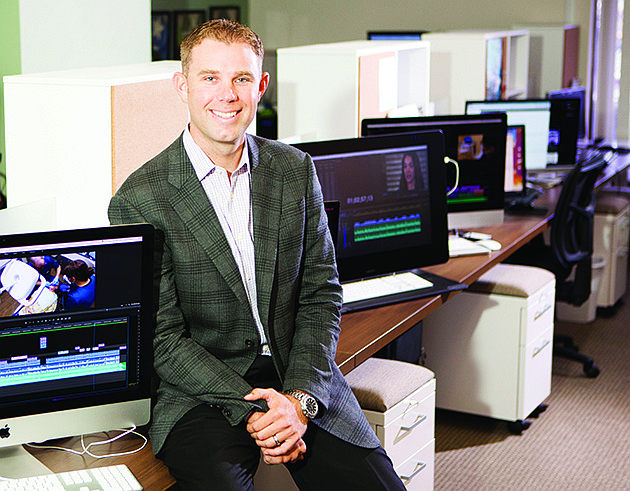

Bart Knellinger grew up in a family of professionals. His father was a dentist; his mother earned a master's degree. Two of his three sisters became dentists; the other an attorney.

But after he graduated from high school, Knellinger decided college required too many prerequisite courses. He set off on a different pursuit: business owner.

To get an entrepreneur's education, he packed up his car and moved to Chicago, because it was, well, Chicago. By the time he arrived in the Windy City, he was out of gas and the $300 he'd started out with was nearly gone.

Fishing for change in the creases of his car seats, a stranger took pity on him at a gas station and gave him coupons for free pizza.

He knew no one, didn't have a place to stay or any leads on employment.

Later that day, at the University of Chicago, Knellinger talked his way into a room for the summer at a near-vacant fraternity house in exchange for a few six-packs of beer. Desperate for a job that would pay him immediately, he landed a gig selling oil changes door-to-door. His first day out, he made $100 in cash — selling 10 changes.

For the next four-plus years, braving Chicago's ferocious winters and paint-curling summer heat working seven days a week, he aimed to knock on 200 doors a day to make a personal goal of 20 sales.

“I would put those four years up against anyone's master's education,” Knellinger, 33, says. “It never occurred to me to stop or get another job. I liked the hustle. I created goals, and went for them. It became a numbers game.”

Just do it

Back in Florida, his uncle helped him get a job at marketing firm selling billboards and yellow pages' ads. Colleagues would typically call 50 people a day to try to generate business; Knellinger would often dial up 450. His first year, he made $150,000.

“I was just more excited about things than they were,” he says. “That's all it was.”

But Knellinger soon realized while he was making a lucrative living, he was held back by his lack of knowledge about the businesses he was selling to, and for.

He began hunting for the biggest marketing opportunity in an industry with the least amount of competition. A conversation with his father led him to dentistry, and specifically, to his father's practice.

Knellinger began marketing restorative packages to clients getting periodontal work. In 18 months, he tripled his father's revenue, which led to an offer from a perio-laser firm that struggled to peddle its $60,000 machines in the Washington, D.C., area.

Within two months — though he didn't know how even to turn the machine on at the demonstration following his first sale — he'd sold four. The secret was simple: With every sale, he'd help the dentists book clients in advance of the machine's installation.

In some cases, the cost of the laser would get covered in a few weeks. Grateful, the dental practices would typically hire Knellinger to provide additional marketing services.

Months later Knellinger flew to Orlando to meet an old friend. The laser sales and associated marketing business was getting too big for him and he needed help. Together, they picked three names off a list of Orlando-area dentists and went cold calling, offering to build websites for them.

It was a great plan, save for one thing: Neither Knellinger nor his friend knew the first thing about website development at the time. Knellinger's own marketing business didn't even have a website. But Knellinger shrugged him off. Clients were buying his strategies, he told his buddy.

They landed all three dentists they saw as clients.

“I look back and I think it was such a blessing I didn't have a product to sell then,” Knellinger says. “Because that forced me to come up with products to meet clients' specific problems.”

His nascent business taking off, Knellinger set up shop in a supply closet in his father's dental practice, and differentiated himself by offering clients training along with marketing.

“My feeling was, I would rather put in a little more time up front to keep a client longer,” he says.

Move forward

The strategy works.

Today, Knellinger's Clearwater-based Progressive Dental Marketing has about 1,000 clients.

“Dentists are terrible business people, by and large,” says Dr. Lindsay Eastman, a Bradenton and Lakewood Ranch dentist who's been in practice 36 years. “And another thing they're not good at is marketing. But in the seven or eight years since we've been with Progressive, they've increased our website presence, our internet presence, big time.

“Bart is very focused, he holds his people accountable, and he has tremendous knowledge of our industry,” Eastman adds. “But mostly, he's a guy who cares about his clients and he's passionate, he loves the results he's able to achieve on their behalf.”

What started as building websites has grown over the years to services including search-engine optimization, videography, social media marketing, web development and specialized account management.

Where many marketing firms turn over as many as 30% of their clients annually, Knelling says Progressive Dental sheds only about 2% of its clientele each year.

“It's all a game of residuals,” he says. “It's how we've expanded so rapidly.”

That lack of client spillage — combined with sophisticated online tracking system that allows for adjustments and an ever-growing menu of new services — has catapulted Progressive Dental forward.

In 2010, the firm notched $170,000 in sales. In 2015, it racked up $6.2 million in sales. This year, it expects to do $15 million.

Referrals from existing clients have helped Knellinger, too, as has attending industry conferences, where the guy without the college education is often invited to lecture dentists about everything from marketing to new medical technology.

In more than one instance, Knellinger's father has showed up at a conference to find his son listed as a keynote speaker.

“We teach them how to sell their products,” the younger Knellinger says.

Knellinger is considering offering clinical training for dentists, and he might even invest in some dental hardware of his own to market.

But those are just ideas; he admits that just like the kid who drove to Chicago, he doesn't have a specific plan.

“Our goal is always to be the first point of contact for the doctor,” Knellinger says. “We want to be the best in every single vertical attached to this business.”