- January 14, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Sean Verdecia came up with the idea of AbleNook, a modular dwelling designed for disaster relief purposes, in 2011 with fellow University of South Florida student Jason Ross.

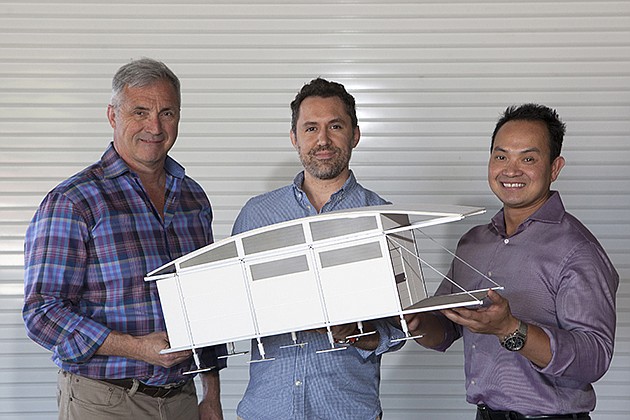

Five years later Ross has moved on to work for his family business and Verdecia has two new partners, Brian Wolfe and Thai Vo. Now the trio, partners at Wolfe Architects, is ready for a new phase at the company: sales

AbleNook is an easy-to-build home, less than 200 square feet, which can be collapsed and conveniently stored. That makes it an obvious product for disaster relief organizations. That potential use has remained, but Verdecia sees a wider customer base. “The market wants it for other uses, too,” he says. “Personal offices, Airbnb, tiny houses. It has many applications.”

The company is preparing to build a full-scale prototype to launch sales. But as architects, the trio knows everything has to be perfect before a deal is closed. “For us, health, safety and welfare all matter, so there's been a lot of development,” Verdecia says.

The process was also delayed, says Verdecia, because the principles were focused on building their architecture careers. Funds to develop AbleNook have come from personal savings and Wolfe Architects.

The disaster relief market, projected to reach $103 billion by 2018, Verdecia says, is a big opportunity for the business. The Federal Emergency Management Agency is a top target customer, in addition to the U.S. Army. Competition comes from trailers.

But AbleNook wants to go deeper than trailers. That's why each AbleNook unit gives the feel of home and can be permanent. As an extra element, front porches are mandatory, Verdecia says. “If a hurricane or an earthquake hits your home, people generally go to a trailer or dome,” Verdecia says. “They don't know how long they'll be there, and there's nothing on the market to give them dignity after a disaster.”

The business model for AbleNook is the company orders the parts, packs and ships them, and the end-user assembles the unit. In disaster relief cases, Wolfe says it could be a group effort to assemble the units. He says “hypothetically, if a country is hit by an earthquake,” the military, volunteers or people who lost their homes could assemble the AbleNooks. He figures the United States would use the National Guard.

One of the key challenges in getting to market has been taking the “architect's ego” out of it, Verdecia says. “The easiest thing to do is make something more complicated. The hardest thing you can do is simplify it.”

Simplifying meant cutting as many steps as possible without sacrificing functionality. Assembly for the end-user takes about two hours. But the pieces pin together and no tools are involved.

Those pins are multi-functional. Correctly assembled, the electrical is automatically connected and walls are fully insulated. Unlike trailers, the pins allow AbleNook units to attach together horizontally or on top of each other, say company officials.

AbleNook units, also unlike a trailer, can be taken apart, repacked and stored, Wolfe says. A standard 192-square-foot unit fits on two pallets. “You can fit eight units on a truck,” he says, “or stack them and store a whole community in one warehouse.”

With development continuing and the disaster relief market growing, AbleNook seeks between $1.5 million and $2 million to build the prototype and fund initial orders. The company is considering taking 100 preorders as an option to help with funding.

Because of the mixed uses, an exact price point has not been determined for an AbleNook. “For disaster relief, they would be priced to compete,” Verdecia says. “Trailers range from $50,000 to $130,000. Ours would be less and would offer comparable options.”

But when people get a chance to customize their orders, that per-unit price goes up. “The bespoke market could be anything,” says Verdecia. “One person wants ostrich leather walls.”

Follow Steven Benna on Twitter @steve_benna