- November 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

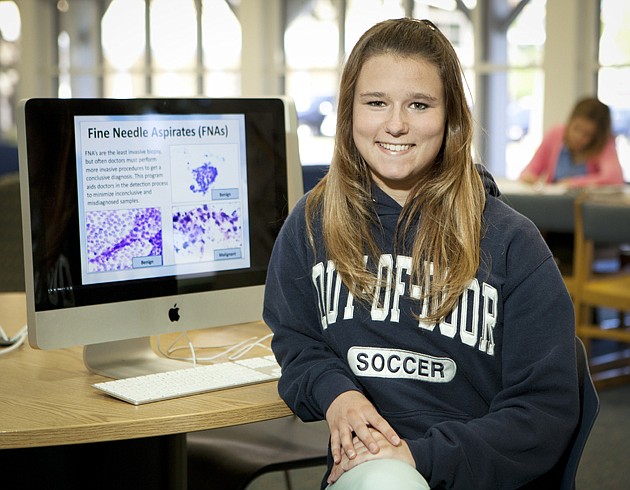

Brittany Wenger, a National Honors Society high school senior who could be headed to Harvard, or possibly Stanford or Duke, might need to rethink her definition of normal.

“I'm basically just your normal teenager,” says Wenger, 18. “I like to hang out with my friends and go to the beach.”

She also likes to play spades with her 14-year-old brother, spend time with her parents and, being that she founded her high school's science club, introduce her friends to new ideas. She volunteers at a camp for kids with disabilities, and she's a midfielder on the varsity soccer team at the Out-of-Door Academy in Sarasota.

Then there's this, something significantly far from normal: Wenger created an artificial neural network, basically a computer brain, that aids doctors in diagnosing breast cancer. A neural network like Wenger's, one that's fed data on a scientific basis, can learn, improve, and even analyze complex equations.

Moreover, Wenger's inventive computer program, now hosted on the website: cloud4cancer.appspot.com, won the grand prize at the Google Science Fair this summer. Wenger's prize includes a trip to the Galapagos Islands, an internship at an institution that hosted the fair, a $50,000 college scholarship and a trophy made of white Lego bricks. She's also set off on a worldwide travel itinerary, from New York to Zurich (See map).

“It was so exciting,” says Wenger of the day she found out she won, which she adds was a surreal blur. “I just sat there bug-eyed.”

Wenger's project, and future potential business, is called the Global Neural Network Cloud Service for Breast Cancer. The program allows doctors to use fine needle aspirates, a biopsy, to determine whether a breast cancer tumor is malignant or benign. The program has a 99.1% rate of diagnosing malignancy correctly, says Wenger.

“It has huge implications,” Wenger says. “When doctors start using it, breast cancer detection will be less invasive.”

The complicated part of Wenger's discovery, or at least one of the complicated parts, was how to use the artificial neural network she built to read and analyze the data. First she found publicly available data on fine needle aspirate tests of breast cancer patients, from places like the University of Wisconsin. She next built several neural networks. Then she ran thousands and thousands of tests — including some where she woke up in the middle of the night to monitor results.

It was during those tests when Wenger learned her first valuable entrepreneurial lesson: Missteps breed triumphs.

“I failed twice before it was a success,” says Wenger. “But I always believed this was a good technology that could help people.”

The urge to help one specific person, a cousin diagnosed with breast cancer, was initially why Wenger put her heart, and brain, into the project. “I've always been interested in the medical field,” says Wenger, “but not specifically breast cancer until I saw the impact it had on my family.”

The next phase of Wenger's project is to partner with hospitals. She recently met with researchers at Lankenau Medical Center in suburban Philadelphia, for instance, about developing a program there. She also hopes to use the artificial neural network platform to help diagnosis procedures with other cancers. After that, Wenger is open to business possibilities, in marketing the program and techniques.

But first, of course, there is high school. That means soccer games, track meets — she runs middle distance for ODA — AP calculus tests, and eventually, college. Wenger hopes to major in computer science and biology, wherever she ends up, and then go to med school. Her ultimate goal is to become a pediatric oncologist. Says Wenger: “I want to be on the team that cures cancer.”