- November 25, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

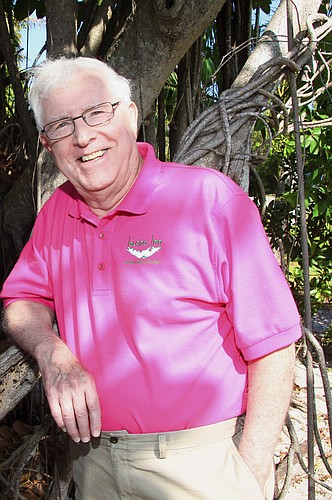

Joe Orndorff, the president and CEO of the Island Inn, wants you to know this about the Sanibel hotel: “There's no benefit to being a shareholder.”

If you're one of the inn's 160 shareholders, you don't get preferential rates, nor do you get to pick the room in which you want to stay. You can't sell or give the share you own to anyone who hasn't been vetted by the board, and each shareholder has the right to only one vote regardless of how many shares he owns. Shareholders get no dividend and don't share in any profits. Even if you were thinking about selling your share, no one will even tell you what a share of the Island Inn might be worth. A shareholder himself, Orndorff's salary is $1 a year.

You've got to wonder: What kind of business is this?

Call it the Island Inn Way, and that was almost its undoing.

It's one of the most unusual corporate structures of any company on the Gulf Coast, especially considering that rooms at the Island Inn cost as much as $340 a night during the winter and it sits on 10 acres of pristine beach on Sanibel Island near Fort Myers that would make any developer salivate.

But this corporate creation that put preservation before profits nearly collapsed after Hurricane Charley in 2004 wiped out the hotel's cash reserves. It was created in 1957, when the island's Matthews family sold the inn to its guests, mostly lawyers from Minnesota who were more concerned about preservation even though they formed a for-profit “C” corporation.

As the original shareholders aged and became absentee owners, however, the hotel slowly began to lose business to rivals on the island. “The hotel was run as a private club,” says Orndorff, who at 73 is among the youngest shareholders.

Hurricane Charley wiped out the hotel's reserves and it suffered through the subsequent economic downturn. By 2009, the hotel's finances were in dire straits. “We were months away from going down the tubes,” says Orndorff, an Illinois entrepreneur who is also president and CEO of Scrip-Safe, a company that provides secure transcripts for 2,200 universities.

Fortunately, Orndorff and other shareholders recognized the financial challenges in time. They hired young, tech-savvy managers in 2010 who immediately upgraded the hotel's technology so it could sell rooms on popular hotel-booking websites.

Revenues doubled in two years, the restaurant is profitable again and the hotel is reinvesting profits into much-needed maintenance. “I don't know how I would've faced my mom and dad if I'd failed this,” says Orndorff, whose parents were among the original shareholders.

Corporate identity

Although it's set up as a for-profit business, the Island Inn's mission is historical and environmental preservation. “The incorporators wanted to keep it the way it was,” says Orndorff, whose parents paid $12,000 for the one share that he inherited. “The deal was that it would be preserved.”

Prospective shareholders must fill out an application that blackballs anyone with a profit motive. “Can you imagine Procter & Gamble doing that with its shareholders?” Orndorff chuckles.

Current shareholders must designate heirs who are vetted so historic and environmental preservation are their only objective. Shares can't be jointly owned.

What's more, the board doesn't publicize the value of each share and isn't interested in buying them back. “The Island Inn isn't a market maker,” says Orndorff. “We don't want to know.”

Orndorff won't speculate about the hotel's value. The Lee County Property Appraiser's latest assessment was $4.3 million, though its location on the beach likely makes it much more valuable.

Over time, the hotel became more of a club for shareholders than a business. Shareholders could pick the specific rooms they wanted to stay in, cancel without penalty and they were not interested in making improvements in technology that many guests expect today. The reservation system was antiquated and guests could not book a room on popular travel websites.

“We had $900,000 in reserves before Charley wiped us out,” says Orndorff, who led the nine-member board after the storm. To stave off financial calamity and a fire sale, the board used the reserves and $1.5 million in storm-insurance payouts to keep the doors open. It also took six hotel rooms and converted them into condo units that it sold and secured a $1.5 million loan from the U.S. Small Business Administration.

Despite the board's best efforts, the hotel continued to lose money. For example, the Island Inn was losing $500,000 a year on its restaurant. “Momentum is a bad thing sometimes,” Orndorff says.

So in 2009 Orndorff paid a visit to Sherie Brezina, the director of Florida Gulf Coast University's Resort and Hospitality Management Program in Fort Myers. She agreed to join the hotel's board of directors, the first outsider to do so.

“There was no doubt in my mind they had to have a significant structural change,” says Brezina, whose objectivity was questioned by some of the shareholders. “People called for my resignation,” she says, adding, “I didn't know those people and they didn't know me.”

Brezina credits Orndorff for persuading longtime shareholders the need to improve the property's operations for its survival. “It's like a family feud because they've been there for 40 years,” says Brezina. “In any organization, change is the enemy.”

Brezina credits Orndorff with the finesse and diplomacy required to make the needed changes. For his part, Orndorff says he operates on the principle outlined by business guru Tom Peters who said it is better to seek forgiveness later than ask for permission now.

Technology boost

Brezina's recommendation was that the hotel invests in a modern reservation system that could tie into popular travel websites such as Expedia. What's more, the hotel needed to adjust rates to price the rooms in real time relative to the competition. “The minute you made those tech changes, you were going to boost those reservations,” she says.

The hotel hired Chris Davison, a 31-year-old general manager, who was one of Brezina's star students. “The benefit of having these younger people in your organization is that it is just innate and second-nature for them,” she says.

Orndorff says it was essential to have a young, computer-savvy executive who was willing to put in long hours on the turnaround task. “A 20-year veteran could've killed us,” he says. Pointing to Davison, Orndorff says: “He's my redemption package.”

The success was swift. In the two years since he's taken over the management of the hotel, Davison says annual revenues nearly doubled to $3 million. He leased out the money-losing restaurant to an independent operator and it's profitable again.

“What it proved was that love and passion couldn't overcome 21st century communication,” says Orndorff. “I personally funded the website.”

With the improved cash flow, Davison and the staff immediately set out to make much-needed improvements. For example, Davison installed flat-screen TVs in every room and Wi-Fi Internet connection throughout the property. “Two years ago that wouldn't have been anything the current board would've paid attention to,” says Brezina.

Davison queried the longtime staff about changes that needed to be made, something that had never been done before. “We did have competitive advantages, and one of them was the staff,” says Davison, who replaced the one-way glass window in the manager's office with a clear pane so guests and employees can see him.

With the board's backing, Davison eliminated room preferences for shareholders and instituted a cancellation penalty that applied to everyone. Some shareholders were unhappy and threatened never to return. “The Island Inn Way is what took us to the edge of the Cliffs of Moher,” shrugs Orndorff, referring to the dramatic Irish cliffs that plunge into the sea. “People understand it in their heads, but not in their hearts.”

Pass it on

While the hotel is profitable again, there's decades of deferred maintenance to perform. Many of the recent changes to the rooms have been cosmetic, but plumbing and other unseen but serious needs require attention.

“We're not out of the woods yet,” warns Davison. “We're dealing with 30 to 40 years of deferred maintenance.”

As the hotel boosts profitability and reinvests the money into making it competitive for the long haul, the company is in a transition of ownership from the older generations. Further complicating matters is that one building on the property contains condos.

“To me the biggest challenge going forward will be combining what the older generation of shareholders want with the needs of the wants of the younger generation,” says Brezina.

Orndorff says he's updated the list of every shareholder with current address, phone numbers and email addresses. In addition, he's identified every shareholder's successor. “We had to go back and do a whole lot of work to do that,” Orndorff says.

Now that it's profitable, the Island Inn can adhere to its preservation mission — and pass it on without financial burden. “I get to visit my mom and dad every time I come here,” Orndorff says.