- November 22, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Fed up with what it sees as reckless spending by Lee County commissioners, a group of retired business executives has launched a public effort to push politicians to reduce their free-spending ways.

Funding for baseball stadiums, conservation-land purchases and six-figure county staff salaries are just some of the multimillion-dollar items this group is targeting.

It's not going to be easy. The county's finances are cobwebs of fuzzy accounting, politicians are well-entrenched and business owners and residents are either apathetic or don't want to risk taking on the political machine.

But anger over government spending is growing and this may be the year voters finally reject freewheeling municipal spending. After all, households and businesses have been forced to make cuts of their own. Why shouldn't government do the same?

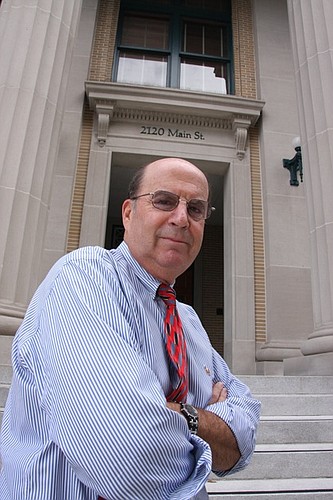

At the helm of this group is Roy Hyman, 64, a longtime banking and real estate executive who moved to Bonita Springs in 2004 to become land manager for national homebuilder Ryland Homes.

Hyman is no stranger to politics. Active in the Republican Party, he was a member of the planning commission of Montgomery County, Pa., the third most-populous county in that state, until 2004. Prior to that, he was director of government affairs and land acquisition for K. Hovnanian Homes and later worked for Barness Organization, whose chief executive was a prominent Republican fundraiser.

Hyman decided to lead a group called the Golden Goose Committee of the Lee County Republican Party after recently witnessing the county overpay for conservation land. The committee had been formed five years ago and produced a report on Lee County's profligate spending that politicians and constituents largely ignored because the economy was so good. “Nobody's watching,” Hyman says. “There's no oversight.”

But Hyman and seven other volunteers are betting that people will be more receptive to their message today. Unlike past efforts by the Golden Goose committee that focused on working quietly behind the scenes, Hyman plans to be more vocal by speaking out at commission meetings and to the media.

“It's money that belongs to us and they're spending it,” says Hyman, who's attended every commission meeting since April.

By Hyman's estimates, about $1.2 billion in taxpayer cash is sitting in county checking accounts earning paltry interest. “It's way too much,” Hyman says. “We would have spent it better in the economy.”

Hyman is worried that Lee County commissioners will continue to spend millions of dollars on projects such as the Red Sox spring-training baseball stadium, overpaying for conservation land and maintaining high salaries and generous benefits for the county staff.

Hyman isn't persuaded by politicians' arguments that most of the money is encumbered for future projects, from libraries to roads. That's because commissioners routinely shift money from one account to another throughout the year, dipping into reserves to maintain a bloated budget by financial sleight of hand.

“It's impossible to follow the money,” Hyman says.

For example, Hyman says you have to be financially astute to decipher the county's 240-page annual budget. “There are things I don't understand,” he says.

Hyman acknowledges that getting people to rally to his cause will be tough.

“Homesteading has made people complacent,” he says. Because of the state's homestead provisions, property taxes for longtime homeowners haven't risen the way they have for business owners and newer residents.

What's more, business organizations have been largely ineffective and business owners aren't willing to risk jeopardizing what little business they do with the county. “People are either trying to survive or enjoying tennis and golf,” he says.

But Hyman argues that Lee's tax-and-spend ways will catch up with business owners if they don't get involved. “I believe the county is anti-business,” he says.

He hopes business owners realize this before it's too late.