- November 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

REVIEW SUMMARY

Business. The Concession Golf Club & Residences, Manatee County.

Industry. Golf clubs, residential real estate

Key. A retired corporate executive is going against market trends by investing millions of dollars into a golf course business.

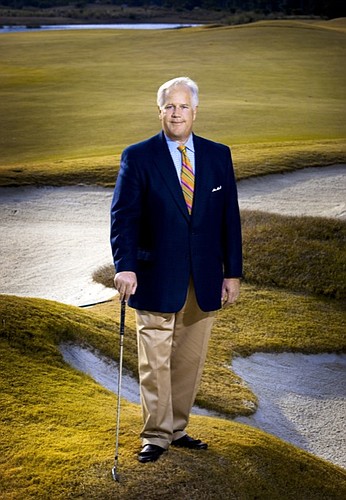

Bruce Cassidy has played on some of the best golf courses in the world, but his home course in east Manatee County could prove to be his toughest yet.

Not just because of the scattered hills, tricky greens and water hazards that make up The Concession, the private-membership course he has lived on with his family since the spring of 2006. Instead, the new, challenges stem from the fact that late last year Cassidy spent millions of dollars to buy the golf club and memberships side of The Concession.

Cassidy, a recently retired steel and mining industry executive, bought majority control of the 520-acre, 18-hole golf course and its newly built, $20 million clubhouse and dining facility. Cassidy bought his stake in The Concession from prominent Sarasota developer Kevin Daves, who will remain a minority owner of the course and the majority owner of the residential side of the project.

“There are other places I could put my money and get a much better return,” says Cassidy. “But I love this club and want to see it do well.”

Cassidy declined to say how much he paid for his ownership stake in The Concession. No matter the price, though, it's a risky bet in what some consider to be dark days for the golf industry, and building homes around golf courses and clubs.

In fact, several Gulf Coast homebuilders that once developed glorious golf club home communities are following a new trend: the retiree that wants to go kayaking, biking and hiking, with golf as just another sport on the to-do list. (See Review, 1/15/10.)

And even in good economies, golf courses aren't profit machines. The operations tend to be high-cost and low-margin.

Still, Cassidy is game to turn The Concession into a success — although he isn't blind to the challenges. The club currently has about 100 members, with plans to cap its fulltime membership base at 300.

“Club membership is a very real challenge,” says Joe Wills, The Concession's general manager who Cassidy hired in December. “It's something we think about and work hard on every day.”

A full membership to The Concession cost more than $100,000 in 2009, a big obstacle to overcome in a recession. That fee has since changed, although Wills declined to elaborate on how much, saying only that the club has “rolled out several exciting new categories of membership to appeal to a broader market.”

Cassidy says an attainable goal would be to sign up 75 full members over the next three years. Attainable, perhaps. Daunting, definitely.

“There is probably no more difficult time to get into the golf club business than today,” says Cassidy. “But looking down three to five years in the future, I think this is a place people will want to be.”

Strategy shift

Cassidy says he plans to spend even more of his money to see that dream come to fruition. “You have to have something people see as special,” he says, in order to outdo the competition.

One avenue toward that goal is The Concession's $20 million, 30,000-square-foot clubhouse and dining area. An official grand opening celebration of the clubhouse, which has been open for a few months, is scheduled for Jan. 23.

The clubhouse, despite its expensive price tag, is actually a byproduct of the recession.

That's because The Concession's original owner, Sarasota developer Daves — who brought the Ritz-Carlton to Sarasota 10 years ago — made a key strategy decision for the club in 2007. That's when Daves decided to pump money into the clubhouse instead of the home sites. He thought the latter would be a losing effort given the residential downturn already underway.

“It was pretty obvious to me that marketing [the homes] was not the answer,” says Daves. “We could have had a $10 million marketing budget and still sold nothing.”

So Daves focused his attention, and financing, on the clubhouse, with the thought that it could ultimately become a magnet to recruit new members. One advantage: The bulk of the construction took place in 2008 and 2009, when few other similar projects were underway on the Gulf Coast. That allowed The Concession to get the lowest rates and the best crews out of Sarasota-based Kellogg & Kimsey, the lead contractor on the project.

Daves sold his majority interest in the clubhouse to Cassidy last summer, in a deal that closed in October. Daves held on to his majority stake of the 1,230-acre residential side of The Concession.

He also held onto his optimism for the project — despite a yearlong dearth of sales and a foreclosure lawsuit filed against him and his development company last year.

The suit, brought by Wachovia Bank, alleges that Daves failed to repay the bank a $22 million loan on the second phase of the residential side at The Concession. The suit doesn't include the first run of homes nor the golf course and clubhouse.

Daves and his attorneys, however, deny the allegations in the lawsuit and have filed a countersuit in Manatee County Court against the bank. Daves says he was current with the terms of the loan agreement and the bank also failed to conduct good-faith negotiations with him and his business partners on other payments and lot sales. “We think the bank is being a predatory lender here,” Daves says.

The case is slowly proceeding to court, although Daves says attorneys on both sides recently held some early stage settlement negotiations. He maintains his belief that when The Concession clears this hurdle and the economy for large luxury homes returns, he and the course will be in great shape.

“There will be a time when these home sites will become viable again,” says Daves. “It sounds crazy now, but the market will change.”

Good eats

In the meantime, the clubhouse at The Concession, designed and decorated by nationally known designers Adrienne Vittadini and Pamela Hughes, is dotted with luxury details. Those include the oversize fireplaces and the plush chairs that make up the card tables outside the locker room.

Says Wills: “There's nothing pedestrian in here.”

And there's also The Concession's Pièce de resistance: The clubhouse restaurant is run by Sean Murphy, owner of the Beach Bistro, an award-winning restaurant on Anna Maria Island. Murphy says he plans to bring some elements of the Beach Bistro out east.

Wills, whose past golf club career stops include a stint as assistant general manager of Augusta National in Georgia, says Murphy's involvement turns The Concession from merely sweet to sublime. “I've worked in a lot of clubs,” says Wills, “and I've never seen a club with a culinary aspect as flawless.”

Wills grew up in the Tampa area and he considers his return to the Gulf Coast to work for The Concession as the pinnacle of his career. That includes his years as vice president of the Sea Island Club in southeast Georgia and his work at Augusta, site of the Masters Tournament.

And then there is the golf course itself.

The Concession course, designed by golfers Jack Nicklaus and Tony Jacklin, has been regularly ranked as a top private course in the country by several industry publications. Golf Digest named it the best new private course in the U.S. in 2006 and the number five overall course in Florida in 2007.

The Concession gets its name from the final hole of the 1969 Ryder Cup Match held at Royal Birkdale in England. That's where Nicklaus, in what is still considered one of the best acts of sportsmanship in the sport, conceded a two-foot putt to the British-born Jacklin. The gimme led to one of only two ties in the history of the Ryder Cup.

Defying doubters

Cassidy, however, concedes little when he plays The Concession.

“I've played a lot of courses,” says Cassidy, who also belongs to the Firestone Country Club in Akron, Ohio, a nationally renowned course that's home to several professional tournaments. “This is my favorite.”

Cassidy, the son of a truck driver who grew up in Steubenville, Ohio, made his money in the steel and mining industries. In the 1970s, with an associate's degree from a local community college, Cassidy got a job as a line engineer for Advance Mining Systems, an Ohio-based company that manufactured steel

beams and products used in the underground mining business.

Over the next 10 years, Cassidy worked his way up in the company to where he was ultimately appointed president and CEO in 1986. He led the company on an expansion into the Midwest and Virginia and it soon attracted potential buyers.

Cassidy left the company when it was sold in 1991. He worried at the time that the new owners were going to drive the company into bankruptcy — a prediction that later came to fruition.

But at that point, Cassidy had already started his own steel company that also catered to the mining industry. That company, Excel Mining Systems, surpassed $200 million in annual revenues by 2006.

Cassidy, thinking ahead to his eventual retirement, sold the company in parts over 2006 and 2007. Not wanting to completely get out of the business life, Cassidy has maintained ownership in several other companies. One of those is a steel business run by his son, based in eastern Pennsylvania.

Cassidy retired from Excel Dec. 31, just in time to focus on his latest challenge: Excel Golf, the limited liability corporation he formed to buy out Daves' interest in the golf course and membership side of The Concession.

Cassidy actually has something of a kindred spirit in Daves: Both businessmen have defied doubters over their careers and share a passion for perseverance.

In Daves' case, he turned an 11-acre site in downtown Sarasota into the Ritz-Carlton, Sarasota, a luxury hotel and condo building that now partially defines the city's downtown skyline. Daves overcame several hurdles to get the project built, only to open in November 2001 during the post 9/11 tourism meltdown.

Actually, Daves is probably saying some of the same things now that he said in late 2001, when the Ritz struggled to get going. One difference now is the name behind the challenge.

“When the market comes back,” says Daves, “The Concession will hopefully start at the top.”

Golf Gurus

The sales staff at The Concession Golf Club responsible for recruiting new members amid a deep recession don't have to go far to find a successful business model.

Indeed, University Park Country Club, about five miles west of The Concession in Manatee County, was one of the first clubs on the Gulf Coast to revamp its business model to meet the new realties of the economy and the industry. University Park, run by a group of Sarasota-area development partners led by Manatee County homebuilding executive John Neal, decided to go from a private to a semi-private membership base in late 2007.

In the process, the club flipped around the traditional membership sales business model. Instead of trading equity stakes for high initiation fees in a complicated and cumbersome process, the club went simple. It designed a series of membership plans built around growing the client base at smaller increments.

“We decided to do the opposite of everyone else,” says John Neal, son of Lakewood Ranch-based homebuilder Pat Neal. “We defied the market.

The defiance worked. University Park has added more than 100 members since it made the switch in November 2007. That growth and momentum has also translated to increased sales on the residential side of the club.

On that front, University Park reported almost 50 new and existing home sales in 2009, up 30% over 2008.

But Charles Varah, a managing partner for the family entity that co-owns University Park with Neal, says the goal of the club's membership transformation was to always mesh home sales with membership. It's a lesson Varah says other clubs should heed.

“The golf club goes hand in hand with the real estate,” says Varah. “Those who forget that will suffer the consequences.”

Neal says one of the biggest signs that University Park's efforts were working came over the past year, when he read the newsletters of some competitors. Other clubs were trying the same approach, Neal discovered.

Still, the transformation came with some big risks. Most notably, Neal and his partners had to pay back the club's 600 equity members a total of $8.5 million, averaging out to between $30,000 and $50,000 per member.

“We were scared, as we should have been,” says Neal. “But the final results show that this was the right way to go.”