- November 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

REVIEW SUMMARY

Institutions. USF and University of Tampa

Industry. Education

Key. Local universities are teaching students about entrepreneurship.

Can entrepreneurship be taught in a classroom?

You might ask Taylor Whitney, a partner at Gibson Consulting; or Chris Kluis, director of marketing at Mintek Mobile Data Solutions; or Mit Patel, owner of MIT Computers. Each has studied Entrepreneurship at the University of South Florida.

Then there are Arthur Linares and Alex Monroe, current Entrepreneurship students at the University of Tampa. Linares is conducting a feasibility study for a product that delivers electricity to parked semi-trucks, while Monroe is working to publish research on the practice of pitching a business.

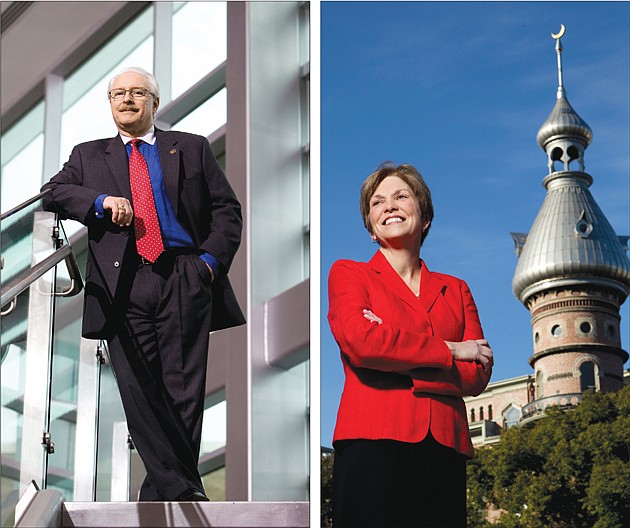

These students are among hundreds who have studied entrepreneurship at a Tampa Bay university. It's an educational trend that is being spearheaded locally by Michael Fountain at USF and Rebecca White at UT, both directors of their schools' entrepreneurship centers.

Both programs are still in their infancies; combined, they've been operating for less than a decade. But Fountain and White stand behind their work, and are enthusiastic about their programs' potential — not just for their students and their institutions, but also for the Gulf Coast.

With concepts like business plan competitions and product development courses, students are working with representatives of local companies to prepare for the business world.

While the two programs have subtle differences in their curricula, both point to a gap in the traditional educational system that could be filled by a new approach to teaching students how to start a business — and simply think in that fashion, rather than simply focus on getting a good job.

Scientific entrepreneurship

Michael Fountain's vision for USF's entrepreneurship program is built on his own experiences.

That vision focuses on the synthesis of business skill, biomedical research and engineering capability into a successful business operation.

Fountain's research experience has taken him from Princeton, N.J. to Silicon Valley to Philadelphia, and has included the formation of seven companies, three of which have gone public.

Here in Tampa Bay, Fountain's work has helped Dermazone Solutions — a company featured in a December 2009 issue of the Review — bring its advanced skin care products to market.

Bringing the fruits of researchers' labor to market drives USF's entrepreneurship program. It's a unique opportunity for biochemists and pharmaceutical researchers with an entrepreneurial itch.

It's a focus that has helped individuals like Kevin Sill, chief scientific officer at Intezyne, make their own waves in the business world instead of signing on with a pharmaceutical giant.

Take the latest addition to the program's curriculum, for example, a class called product development. Inside, students work with existing companies to design and test innovative concepts that fit real-world needs.

Other classes take on challenges like patents and federal compliance — think FDA approval for a drug. They're concepts that you wouldn't learn in either a chemistry lab or an MBA setting.

Put it all together and you get a unique educational opportunity that Fountain calls “a truly green field to plow.”

Given the program's specialty, it's interesting to think about the consequences of poor business execution for medical researchers. As Ferdian Jap, the USF Entrepreneurship Alumni Society's president, points out: “The next cure for cancer may fail if it's not brought to market correctly.”

Of course, many business concepts do fail. Fountain argues (and students interviewed for this story all agreed) that the opportunity to have a business model torn to shreds by experienced professionals in an environment with much lower risk is a useful preparation for aspiring entrepreneurs.

The practice helps students separate the entrepreneur from the business idea, an important lesson for the risky business that is entrepreneurship.

“You're invested,” Fountain tells his students, “but you are not the venture.”

Undergraduate pressure

At the University of Tampa, Rebecca White is just as big a fan of exposing young students of entrepreneurship to intense scrutiny.

One of the more recent additions to UT's entrepreneurship curriculum takes students from a 90-second concept pitch to a business plan over the course of a semester. The key there, White says: exposing students to pressure.

Also on the agenda are business plan competitions, where local experienced professionals will judge students' original business concepts.

White has recently dealt with some pressure of her own, having assumed her directorship in August of this past year. But already, she's instituted successful changes that could help the school's entrepreneurship program grow.

Growing an entrepreneurship program is something White knows all about, having spent the last 15 years building an entrepreneurship curriculum at the University of Northern Kentucky, just across the river from Cincinnati.

When she first started at UNK, the subject was getting little traction at most schools. “Entrepreneurship education is relatively new,” White points out. But lessons from that experience have helped shape the direction of UT's program.

Similar to how USF is working with medical researchers and engineers to start their own businesses, White's focus is on teaching entrepreneurship skills to undergraduate students with varied educational interests.

While still in Kentucky in 2002, for example, White helped create an accounting class for non-business majors, which taught students basic budget-balancing principles.

This year, White is pursuing an opportunity for entrepreneurially inclined students to pair up, business students with non-business students, to formulate business plans.

It's a key part of starting a company that most small business owners know of firsthand: the ability to construct, communicate to, and collaborate with a team of business professionals.

White knows just how important the skill is from having hired a chief executive officer for her own company.

She co-founded a business called Risk Aware, which provides security services to higher learning institutions, in 2006, and hired a CEO two years later.

(The company's mission took on a heightened personal significance for White a year later when tragedy struck campus at Virginia Tech, where she had received her MBA and doctorate.)

That business continues to do well, but White's focus remains on what she feels is her true professional calling. “I'm a faculty member at heart,” she says.