- November 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

REVIEW SUMMARY

Company. Celestar Corp.

Industry. Defense consulting

Key. Keeping track of foreign enemies and its own volume

By the Numbers. Click here for revenue information on Celestar.

The inside of Celestar Corp. doesn't look anything like the Counter Terrorism Unit on Fox's “24” — no fancy lighting, no elaborate satellite feeds and no Jack Bauer-like characters running around with intensity.

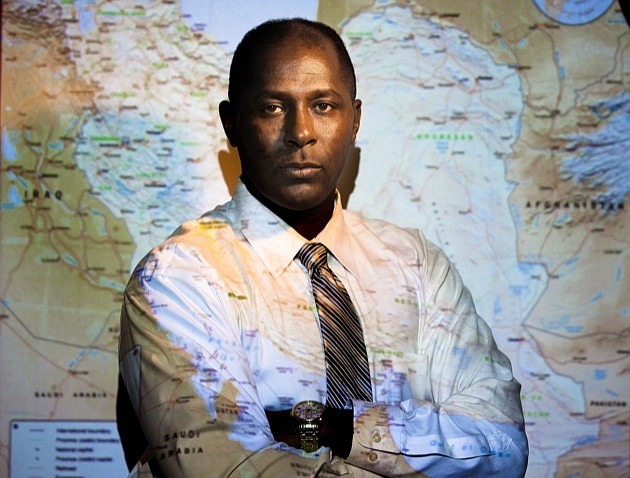

Greg Celestan, chairman and CEO of the Tampa-based company, is as low key a leader as one may expect to meet for the type of work done by a Defense Department contractor. Military intelligence is certainly serious business, but he says it isn't necessary to take it too seriously.

“It's very interesting work, but it's a lot of mundane work,” the former Army lieutenant colonel says with a smile. “My personnel don't carry weapons or kick down doors.”

Based in a low-key building near the huge cloverleaf interchange of Interstate 4 and U.S. 301, Celestar has 15 employees there among 100 also working at military installations such as MacDill Air Force Base and Fort Bragg, N.C., and at an office in Washington, D.C. It also provides consulting services to governments in the Middle East, all the while gathering what Celestan terms as “predictive analysis” on potential threats to the United States.

Unlike the fast pace of fictional television dramas, real intelligence gathering can take months or years before troops and authorities are able to execute a mission that makes news stateside. But even though Celestar (a play on the founder's name, credited to his daughter) tries to keep a low profile, it doesn't have to operate in complete secrecy.

Its blink-and-miss-it building along U.S. 92 has the corporate logo right out front and nothing classified is contained there.

Rather than keeping themselves cloaked in secrecy, its employees are involved in local charitable efforts supporting the military, such as Operation Helping Hand at the James A. Haley Veterans Hospital or Project Athena, which assists female veterans with post-war problems. Many Celestar employees are veterans and well understand the challenges of transitioning to civilian life.

“Most of us live in the community, but we work behind closed gates and doors at MacDill,” Celestan says. “We do our jobs, then we go home.”

Gaining recognition

Celestar's public profile is no longer as low as it once was. The firm received an Ernst & Young Florida Entrepreneur of the Year award, making it eligible for national recognition, and also made last year's Inc. 500 list of the nation's fastest-growing companies. It was also spotlighted recently in The Washington Post's “Top Secret America” investigation of companies launched since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

As its services become in greater demand, Celestan says the challenge is not to grow too quickly. Its annual revenue jumped quickly over the last decade to nearly $12 million and can potentially go higher as federal and foreign agencies need help.

Thousands of companies like Celestar compete for defense contracts, though most are small and address specific skill sets such as counter-terrorism or special forces, according to Celestan. However, he says some of them only stay in business for so long before they get out or sell out to a larger firm.

“It's very difficult to get started in this business because you need security clearance and the government likes to see evidence of past performance,” he says. “They don't want to let a contract of this nature and find out in the middle of it that you can't do it.”

Celestar's latest announced contract is part of a team led by Fairfax, Va.-based SRA International Inc. to provide support services to the Defense Intelligence Agency. The contract is potentially worth up to $6.6 billion over five years, divided among 11 award recipients.

The biggest challenges to Celestar's growth is maintaining its agility and value-added service while balancing the company payroll through good or bad times. “We want to be a jet ski, not a supertanker,” Celestan says. “I don't want to get so large that I don't know everyone in the company.”

Prior experience

During his 20-year military career, Celestan published numerous articles on foreign threats and was team chief of the Unconventional Targeting Cell, which developed intelligence against high-value Al-Qaida and Taliban targets. Recognizing the demand for such services from the private side, he launched Celestar in 2001 in a bedroom of his home, working nights and weekends before retiring from the Army in June 2004.

Instead of seeking outside investors, he funded the startup entirely out of pocket, using credit cards and savings accounts. He says he wasn't able to secure a credit line starting out, but has one now to help with things like renovations to its current building.

“We've always been in the black,” Celestan says. The single-employee operation secured its first contract the following month and began growing quickly, from $50,000 in 2004 to $250,000 in 2005, when he began hiring, then $2.5 million in 2006.

“We want to be able to operate without any wild swings or layoffs,” he says. “Even though it's been a steep growth pattern, it's one that I can manage.”

Despite being on Tampa's outskirts, Celestan says its proximity to MacDill is helpful in recruiting employees and securing contracts, along with being close to Tampa International Airport. He says the firm once won a contract when the prospective client asked for a face-to-face meeting within 24 hours on a Friday morning and his team was able to fly out that Thursday night.

Its biggest victory to date, he says, is a long-term contract with the United Arab Emirates, with which he used to coordinate training while with U.S. Central Command at MacDill. The UAE officers wanted to expand on those services, which wasn't allowed under military guidelines, but Celestar was able to help once it was up and running.

'Too bullheaded to fail'

Celestan credits president and COO Ralph Roome, also a retired lieutenant colonel from the Army and a former CentCom colleague, with securing the UAE contract, which is in the process of being renewed another five years.

“The reality is we got in the middle of it and said let's keep going,” he recalls. “We were just too bullheaded to fail.”

Having been a subcontractor to Bethesda, Md.-based Lockheed Martin Corp. early on, Celestar tries to maintain the same qualities it started out with, such as adding value to its services, working late when necessary and making “yes” its most frequent answer.

Being able to meet directly with clients is also important: “It's important that they see us,” Celestan says.

While Celestar is technically still considered a small business, it is endeavoring to operate like a larger corporation. Celestan serves on the board of directors of the Greater Tampa Chamber of Commerce and often attends business seminars, mostly to find out how other companies have grown.

“I still feel like I have a lot to learn,” says Celestan, who was genuinely surprised by the Ernst & Young honor. “I don't think we're anywhere near where we can be. That award is something along the path, but we're nowhere near the goal yet.”

In taking a quick glance at some of the group photos at Celestar's offices and website, one might take notice that Greg Celestan is the only person of color present — and he's the boss.

It doesn't bother him that the company hasn't garnered widespread recognition as a minority-owned business in the Tampa Bay area. That status certainly helps in competing for business with federal agencies, but he says it isn't a primary concern.

“It gets us in the door on some contracts,” he says. “After that, we have to perform. Let's not focus just on being the best black-owned business in Hillsborough County or Florida, let's focus on being the best business.”

Celestar is also able to claim Service Disabled Veteran Owned Small Business status because of a prior leg injury sustained by Celestan, which allows it to compete for other set-aside contracts. But he specifies that securing a contract is less important in the long run than being able to perform.

“Regardless of what type of business you are,” he says, “if you fail and get a bad reputation, you're toast.”