- November 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

REVIEW SUMMARY

What. Ed Marin moved his company from California to Sarasota because of fewer taxes and regulations.

Company. Soicher-Marin

Key. Taxes and regulation really do make a difference for companies.

Business owners and executives who lament the difficulties of running a company in Florida can take solace in this fact: At least this isn't California.

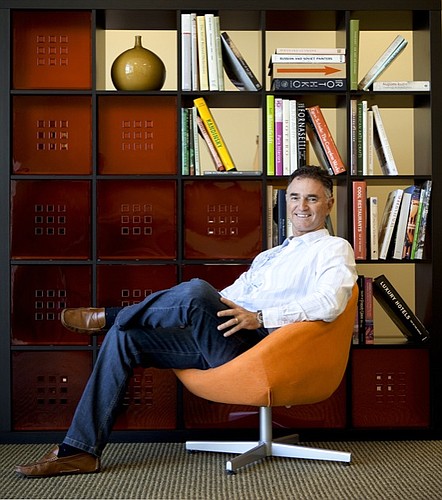

Ed Marin knows that firsthand.

He moved his Los Angeles-based art and commercial wall decor company, Soicher-Marin, to Sarasota last November. The company sells framed artwork to a variety of commercial real estate clients. The list includes office landlords such as CB Richard Ellis and department stores such as Nordstroms and Kohl's.

Marin's move from his native state, the place where his father co-founded the company in 1957, followed a decade of winces and cringes at every government-induced cost increase that came his way. The sales tax in Los Angeles County, for example, is 11% and seemingly still climbing.

“California is a very business-unfriendly environment,” says Marin. “Anything you see on TV or read about in a newspaper doesn't begin to cover how difficult the state has made it to run a business.”

Still, Florida, and the Gulf Coast in particular, is littered with businesses that struggle to succeed against what some perceive to be an anti-business mentality. Collier County and its daunting impact fees, some of the highest in the state, is but one example. Sarasota County, while it has made some recession-era changes, also has a reputation for anti-business.

Marin, however, says it's all about perspective. “The Florida businessman might not have an understanding of how bad it could be in other places,” he says.

For instance, Marin is says he will save at least 33% on workers compensation fees in Florida. The cost for his office and manufacturing space — 30,000 square feet in an industrial and corporate complex near the Sarasota-Bradenton International Airport — is also down significantly.

And of course, Florida, unlike California, has no state income tax.

Marin considered moving Soicher-Marin to other locations, such as Chapel Hill, N.C. and Austin and San Antonio in Texas. Marin and his wife ultimately decided Sarasota would be the best move for the business while still allowing them to live the coastal lifestyle they desired.

When Marin first sought a new location for Soicher-Marin, it was originally going to be a satellite office. He wanted to keep the office in California and have another facility to handle shipments headed east of the Mississippi River.

But when the economy tanked in 2008, Marin decided the time wasn't right to have two offices. He settled on Sarasota. He relocated four employees to the area in the move, including the head of operations and a vice president of sales. The company maintains an independent national sales force of about 25 people.

Marin is aided by the fact that his business could essentially be run from any state. The company has a digital library of 15,000 prints it turns into custom-framed works for clients through handmade stitching and framing done on a spacious factory floor. It then ships the art to the location, occasionally sending a team of employees to hang and place the art.

Soicher-Marin also recently launched a custom framing business, which is available to local interior designers and retail customers. Artwork sales, however, remain the company's forte.

In addition to department stores and office buildings, Soicher-Marin has several homebuilding clients, for which the company sells art for model homes. Those clients include Naples-based Landmark Development Group and Lakewood Ranch-based Neal Communities, one of the leading homebuilders in the region.

Marin says the company's fortunes are directly tied the real estate market, both commercial and residential: When buildings are going up, people need art and mirrors to go inside.

So the recession has dented the company's growth. Marin declines to release specific annual revenues, only to say it's between $5 million and $10 million — a figure down at least 33% from its 2008 peak.

“We need real estate to come back in a big and meaningful way,” says Marin. “We need developers to developer again.”

Ed Marin had already thought hard about escaping the high costs of running a business in California on Election Day in 2008.

His epiphany came that day, however, when Golden State voters overwhelmingly approved a $10 billion bond initiative to be used for high-speed rail.

The project involves a long discussed 340-mile rail line from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

It cemented Marin's belief: California is a banana republic. The state was already billons of dollars in debt when the initiative passed.

“You don't go borrowing more money when you can't pay back the money you already borrowed,” says Marin, who moved his company, Soicher-Marin, to Sarasota late last year. “California can't just print money like the federal government can.” Marin moved his artwork sales company from California to Sarasota late last year.

Of course, when he came to Florida, Marin traded one potential high-speed rail project for another one. At least from a taxpayer cost perspective Florida's project is a comparable bargain.

That's because the Sunshine State's rail project is so far only valued at $1.25 billion — federal money promised by the Obama Administration.

Sarasota attorney George Mazzarantani isn't on a local economic development payroll. But he sure could be.

Mazzarantani has played a pivotal role in enticing several businesses to move to Sarasota over the past decade. A friendship he had with Pittsburgh real estate executive Helen Sosso, for example, indirectly led her to open a new office in Sarasota. That office, Prudential Palms Realty, is now one of the largest real estate firms in the area.

Mazzarantani's latest coup: He enticed Ed Marin to move his $5 million artwork sales firm to Sarasota from California.

“Economic development shouldn't be a buzz phrase,” Mazzarantani says. “It's something we all should be doing.”

There are certainly organizations in every Gulf Coast county that do that, but Mazzarantani is a rare find in that he doesn't charge a business tax for the service. He does it for free, although Mazzarantani now represents Marin in legal matters.

Mazzarantani and Marin have known each other through business contacts for 20 years, going back to when Mazzarantani was a Miami-based architect. So in 2008, when Marin told Mazzarantani he was thinking about leaving California, the attorney went into what he calls “war book” mode.

He wrote a series of memos on why Sarasota would be the best place for Marin to relocate his business. And when Mazzarantani writes these memos, he doesn't harp on the obvious, like the region's beaches and cultural offerings.

Instead, Mazzarantani focuses on the financial and logistical issues. He caters the memos to the specific business and he lists the cons with the pros.

Marin was impressed.

So much so he moved his company, Soicher-Marin, to Sarasota late last year. And after being in town six months, Marin thinks local economic development groups would be wise to follow Mazzarantani's lead, especially in his former home state.

“They aren't poaching it actively in California,” says Marin. “They should be out there killing it.”