- November 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

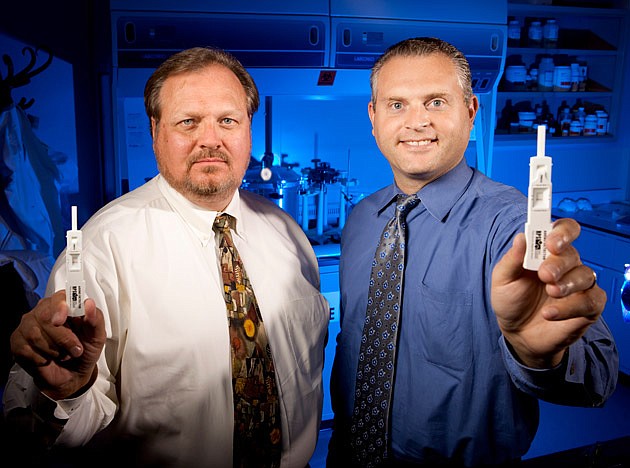

To the untrained eye, the stick Thomas Orsini holds in his hand as many as a dozen times a day looks like nothing more than a home pregnancy test.

But to the trained eye of an ophthalmologist, or even a pediatrician, the stick is a potential medical breakthrough: A lab-quality device that can detect acute conjunctivitis, more commonly known as pink eye. Unlike tests for other medical calamities, an in-office pink eye exam that can be conducted in 10 minutes or less has never been done before.

And to Orsini, the stick holds even greater potential: It's his hammer in the battle to beat back the recession while also serving as a tool he can use to bring a real low-cost solution to the raging healthcare debate.

“We are coming out with a new development that we believe will change how a physician will perform medicine, [so] there are a lot of opportunities to leverage this,” says Orsini, chief executive of Lakewood Ranch-based Rapid Pathogen Screening. “We're trying to go places with this where no one has been before.”

Orsini is confident one of the places RPS will go is into $100 million annual revenue territory — a lofty forecast he nonetheless says could happen within four years. So far, the company has had to settle for more modest startup-like revenues: It's projecting $5 million in 2009 revenues, up from a little less than $1 million in 2008.

Most of the company's sales have come from government and military contracts, although it's in the early stages of executing a sales strategy to reach both family medical practices and ocular offices.

It also recently signed a deal with MinuteClinic, a chain of health care clinics inside CVS stores. The agreement is for MinuteClinic to use the RPS pink eye detector in 23 of its locations in and around Atlanta as a test run to one day possibly expanding nationwide.

Big savings, fewer drugs

The source of Orsini's optimism is the RPS Adeno Detector, the stick that looks like a drugstore pregnancy test. The patent-protected detector has been cleared for medical use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, has its own Medicare reimbursement code and was recently written up in the Red Book, a manual of infectious diseases published by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

RPS physicians have also talked up the Adeno Detector in front of the Super Bowl of medical crowds — a room full of physicians at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

Orisni's medical side partner at RPS, Sarasota ophthalmologist Dr. Robert Sambursky, thinks all of this exposure and recognition of the product is great for business.

But Sambursky also looks at the RPS pink eye detector from the eyes of a doctor who knows that pink eye, due to its varying causes and symptoms, is one of the hardest diseases to diagnose and treat. Many of the current tests on the market can also be painful for children to go through.

“Clinicians have always had a hard time diagnosing this,” says Sambursky, RPS' chief medical officer. “Our device does it in 10 minutes with only a small amount of tears.”

Not only that, but Sambursky says the RPS Adeno Detector provides a secondary, but still important benefit to the medical and healthcare community. That is, a test like the RPS one that can easily — and with a 92% accuracy rate — detect pink eye can be a valuable weapon in the war against overprescribing antibiotics. As it is now, Sambursky says many doctors will subscribe antibiotics for pink eye, even though it might only be necessary 40% to 60% of the time.

So the RPS Adeno Detector, says Sambursky, “will not only result in better patient care, [but] it will also save millions in health care dollars.”

'Made it better'

Sambursky is part of a family of ophthalmologists, an eye-doctor clan that includes his brother and his father. And a discovery made by a family friend in the biotechnology industry, Robert VanDine, led to what is now the current version of the RPS Adeno Detector.

The discovery happened earlier in the decade, when VanDine heard about a German biotech company that was developing new technology for drug tests. At first, VanDine and the ophthalmologists worked in tandem with the company to develop pink eye detector tests.

But by 2004, the team of eye doctors had decided they could do better on their own, so they bought some of their German counterparts technology and brought it stateside. The Samburskys used about $100,000 in family money and savings to get things going.

Says Sambursky: “We took it and made it better than it was.”

The independent entity opened an office for marketing and distribution in central Pennsylvania and in 2006 it opened a laboratory in Sarasota, where Sambursky lived and practiced medicine. The lab back then housed just two employees.

The current version of RPS has 22 employees that work out of its facility in a Lakewood Ranch corporate park, in addition to five employees who work in sales and marketing in other parts of the country.

As RPS has grown its portfolio of physicians, lab clinicians and medical sales professionals, its need for capital has also grown. It has raised at least $4 million in funding over the past few years, most of which has come from angel investors outside of Sarasota.

The company is also growing its presence in new markets by using its products for other medical tests. For instance, it recently signed several contracts to provide tests that can help military agencies detect chemical warfare nerve agents. RPS executives also hope to eventually expand the product line to include tests for the root causes of fever and other hard-to-detect viruses.

One looming challenge RPS faces is one that many businesses selling a new technology or product face: Educating consumers, in this case doctors and healthcare administrators, that there is something new and better out there.

Sambursky says the ophthalmology world, like a lot of medical professions, is entrenched in tradition. Says Sambursky: “We have to educate people that there is a new perspective.”