- November 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

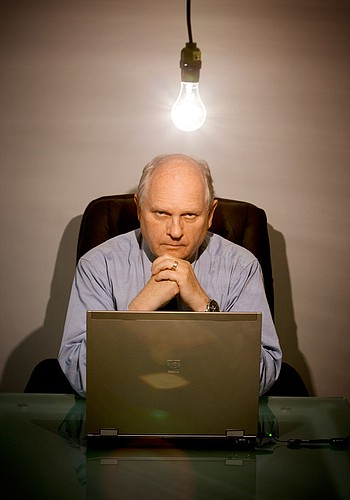

Small business owner John Jorgensen is at the front door of entrepreneurial purgatory: He's got a growing pile of customers that can't, or won't, pay their bills.

Indeed, more than $120,000 in revenues has gone uncollected over the past year, which isn't mere pocket change for Jorgensen's $1.2 million company, Sarasota-based Sylint Group. The nine-employee firm performs a combination of computer-related services, from selling software and setting up networks to tracing a system's digital data history for civil court cases.

Jorgensen realizes going after the customers for the bills will likely be a futile exercise. Still, he isn't content to simply call the accounts duds and moving on, as many other Gulf Coast businesses have been forced to do during the recession.

Instead, Jorgensen, 64, has developed a somewhat risky approach to pad Sylint's recession survival strategy.

He's paying it forward — way forward: He's told most of Sylint's unpaid clients that he will carry their bills for at least another year, maybe longer. And not only that, in some cases Jorgensen has told his staff to do even more services for some of those clients who haven't paid up.

“It's not the Harvard Business School answer,” quips Jorgensen.

But it's a combination of pragmatism and philanthropy that he hopes will be paid back in full one day when the economy rebounds. It's pragmatic, he says, because extending what is basically unsecured credit to a company is better than haggling for 10 cents on the dollar in bankruptcy court.

And the philanthropy is served a la carte, not at an all-you-can eat buffet. “We think it through with each client,” says Jorgensen. “These are clients that have given us sustained income over a long period of time and their business critically depends on our services.”

The risk, of course, is that Sylint's unpaid accounts grow into long-term IOUs. One Sylint client, a company not included in the reprieve program, recently filed for bankruptcy, costing the firm about $12,000 in lost fees.

Gear and gadgets

Risk-reward analysis is old hat for Jorgensen and most of the associates that make up the Sylint Group.

The Boston native worked as a defense contractor for the National Security Agency for 25 years and has hired several folks with an alphabet soup-laden government background. The Sylint crew includes a former FBI agent, a one-time CIA analyst and the most recent hire, a 17-year computer forensics investigator for the Florida Deptartment of Law Enforcement.

And when it comes to risk, Jorgensen is planning worst-case for the recession, in terms of when it will end. As such he is also focusing on a second unit of Sylint's business, the sexier — and more lucrative — one of digital data forensics.

In that department, Sylint serves as a time cop in the tricky world of computer hard drives and server mainframes. It does that by using specialized in-house assembled computers that can trace a system's history, almost all the way back to the assembly line where the first chip was installed.

The company has worked nationwide, mostly for law firms on the plaintiff side of civil cases involving some sort of alleged computer malfeasance, from employee theft to stolen trade secrets. Work it did on one recent case, for a steel company in a data theft recovery lawsuit, was cited in Westlaw, a well-read legal journal.

Locally, Sylint is involved in two high-profile government cases.

The company was recently appointed as a special master in a case in Sarasota County court involving a Venice citizen who sued city council members for allegedly violating state open meetings and communications laws. It also has been hired by a Sarasota law firm for an ongoing civil case into missing computer files from the Sarasota County Sheriff's Office.

“Our goal is not to be a hired gun like so many other so-called experts out there,” says Vince Dellaccio, a forensic engineer and investigator at Sylint who previously worked for the FDLE. “When we conduct an investigation, we do it as an intelligence operation, not just a forensic case.”

The approach pays well.

Jorgensen's firm charges $225 an hour for forensics work, $285 an hour for senior-level work and $350 an hour for testifying in court. The company made $800,000 for work it did in the steel case, spread over three years.

The revenues come at a high-cost, though, as Jorgensen says to be one of the best in the field he has to have the best gear and gadgets. The company has about $300,000 in hardware and software at any one time and rotates $50,000 in equipment every year. And its trio of in-house built computers, which it uses for sensitive forensics work, runs $20,000 per machine.

'Competency control'

Jorgensen founded the Sylint Group in 1999, after retiring from government work and moving to the Sarasota area. His son Serge Jorgensen, who attended the U.S. Naval Academy, joined Jorgensen in the company and is still a principal in the business today.

The company has grown revenues about 20% a year almost every year since it was founded, John Jorgensen says, even through the recession. The company is also projecting growth in 2009, to about $1.7 million in revenues, not including the unpaid accounts receivables.

The growth could have been faster, says Jorgensen, but he deliberately slowed it down and turned away clients during the boom, as he knew more work meant more hires. And he has a fanatical approach to how he “controls the competency” of his employees, so that his hire matches his expectations and the company's needs.

“It's hard to find people with the experience and capabilities we are looking for,” says Jorgensen. “We just can't hire an IT person or a software developer.”

Not surprisingly, Sylint takes the clandestine approach to hiring. If it gets an applicant or hears about a potential hire, Jorgensen and his team will watch the person work, either in open court or by reading his work. If it likes what it sees, it brings the person in for an interview and then a test run.

Says Jorgensen: “We are very particular about who we bring on.”

Jorgensen says he's broken his self-imposed hiring rules twice and both times he ended up firing the employee. One time he brought on a recent college graduate who just didn't have the skills and work ethic. Another time the company hired a candidate only on a high recommendation.

Jorgensen chalks up the hiring mistakes to an entrepreneurial lesson learned. “If you set up a set of rules and the rules work,” says Jorgensen, “don't violate the rules.”