- November 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

It takes a long time, apparently, to become the Velcro of the beverage can, coffee cup and soup container industry.

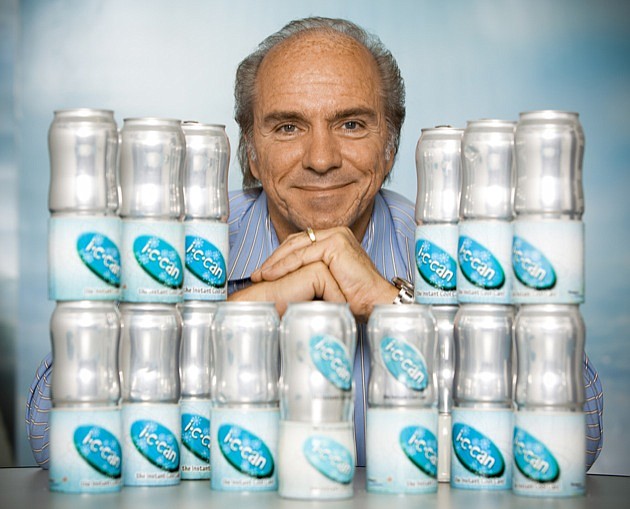

But waiting is nonetheless the spot Barney Guarino finds himself in these days.

Guarino's firm, Bradenton-based Tempra Technology, has been lauded locally and nationwide for its patented and proprietary self-heating and self-cooling technologies. The company is a past runner-up for the Review's Technology Innovation Award, and Guarino is a past finalist for the Review's Entrepreneur of the Year Award.

One of its core products is the Instant Cool Can, which lowers beverage temperature by at least 30 degrees in about three minutes through the use of water evaporation. Guarino claims it's the world's first and only “commercially viable self-refrigerating can.”

Another Tempra product, on the opposite side of the temperature spectrum, is a pouch-package that automatically self-heats to warm the contents when it's squeezed.

But the 17-year-old company, despite several close calls over the last five to 10 years, has yet to fulfill the lofty goals it has set in terms of licensing sales. Tempra, which has raised $27 million in investment capital since it was founded, has also passed on at least half a dozen opportunities to sell its patents or go public in a reverse merger.

“If you take a look at the calendar, it does seem like a long time,” says Guarino, who bought Tempra in the early 1990s after meeting the original founders while an investment banker for Morgan Stanley. “But for me it doesn't seem that long because of the excitement and enthusiasm for the company.”

That, and Guarino is a stubborn New York transplant who considers the company's mission — to bring in tens of millions of dollars in annual revenues through licensing and royalties — the ultimate entrepreneurial challenge of his business life. Even more of a challenge than the late 1980s, when, with Morgan Stanley, Guarino worked on the complicated financing project for what is now the St. Petersburg Times Forum in Tampa.

But the Tempra challenge, it turns out, might intersect with opportunity over the next 12 to 18 months: The company recently signed a $2.5 million deal with a large global food and beverage company that wants to study and test Tempra's proprietary coffee cup. Guarino declines to release the name of the company, citing confidentiality requirements.

The deal represents a breakthrough for Tempra. For one, the company it's working with won an international bidding war for the rights to get a peek at the internal workings of the Tempra coffee cup. To Guarino, that shows progress in industry validation.

Moreover, the contract with the food and beverage company has this juicy provision: If the company decides to take the cup to the mass market, it will pay Tempra $15 million in royalty fees.

Tempra has also sought other opportunities for licensing deals. It has targeted several other areas for its products, including the U.S. military, the global aviation industry and the cosmetics and personal care industry.

From a military perspective, Guarino says Tempra's self-heating technology would solve a big issue for soldiers that are unsatisfied with cold Meals, Ready to Eat (MREs) in the field. Tempra has successfully tested its MREs with the U.S. Army and is working with a company to develop a large-scale manufacturing process for the products.

In the meantime, Guarino keeps waiting and working. He tells his staff to set small goals on big projects, which is what he tries to do as well.

Guarino is also emboldened by a story he recently heard from John Lilly, a former Procter & Gamble executive who recently retired as chief executive of the Pillsbury Co. Lilly heard about Tempra through industry contacts, met with Guarino and is now an adviser to the company.

Lilly told Guarino it was almost a badge of honor at P&G to see how long it could take for a product to go from concept to supermarket shelf. Take Pringles potato snacks, which, according to Lilly lingered in the research and testing phase for 17 years before making its grocery debut in the late 1960s.

“It has been difficult,” says Guarino. “But that [story] was my salvation.”

— Mark Gordon