- November 22, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Hold onto your wallets, you could be in for a bumpy ride. Consider this conclusion from Randal O'Toole:

“Rail transit and intercity high-speed rail are expensive programs that require huge subsidies and provide little in the way of energy savings or other environmental or social benefits,” writes economist O'Toole in his 2008 Cato Institute paper entitled, “Rails Won't Save America,”

Yet, America, Florida, Tampa Bay and central Florida are all poised to embark on a multi-billion dollar spending spree on light rail and commuter rail projects. Commuter rail generally operates with diesel locomotive engines pulling passenger cars from outlying areas to central urban areas, and light rail systems carry smaller groups of passengers within an urban area.

They have a long history of being way over budget and even further under-utilized. On average, these rail projects cost 40.2% more than first estimated, and as a group, have delivered less than 60% of predicted riders according to a year-old Federal Transit Administration (FTA) report.

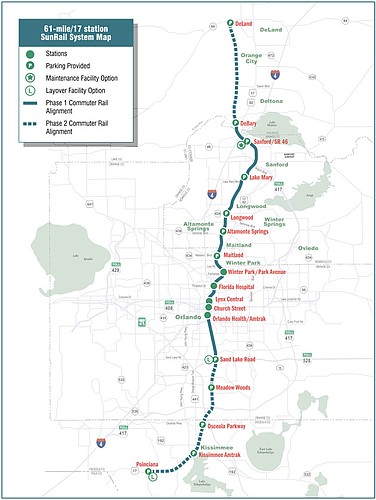

Central Florida's controversial SunRail project would use the existing 61-mile A-line owned by CSX, and estimated to cost $1.7 billion, plus another $948 million for operations and maintenance out to 2036. The plan includes 17 stations from

Deland through Orlando and Kissimmee to Poinciana that State Sen. Lee Constantine, R-Altamonte Springs, claims will have a $7.3 billion economic impact and aid in creating 246,000 jobs.

The state would buy the tracks from CSX for $150 million and pay $491 million more to upgrade CSX facilities, including tracks for freight trains on the S-line, which runs from Duval County through Ocala to Plant City and Lakeland. At nearly $10.6 million per mile, the $641 million payment to CSX ranks as the highest price ever paid per mile for rail in the United States.

Sen. Paula Dockery, R-Lakeland, and her husband, C.C. “Doc” Dockery, have fought for high speed rail in Florida. Sen. Dockery also favors commuter rail, but she adamantly opposes this deal. According to documentation she assembled about SunRail, there are 17 issues that the FTA says must be addressed with 13 still unresolved.

Commuter and light rail plans of the Tampa Bay Area Regional Transportation Authority (TBARTA) are not as advanced, but could cost as much as $12-23 billion. A $192 million sales tax increase proposal, which may go to referendum in November 2010, is in the pipeline for Hillsborough County. Pressure will be on the other six counties to get on board.

$375 million gap

For SunRail, the $703.4 million state share will cost more like $800 million, according to Sen. Dockery, after adding in bonding costs. Complicating matters is uncertainty over half its federal funding.

Only $178.6 million is part of the Florida Department of Transportation's federal application. But even with an additional $129 million expected to flow from the FTA to cover the rest of the initial capital cost, that still leaves $375 million of questionable federal funding that SunRail must compete for.

If those dollars don't materialize, the state and central Florida local governments involved will be on the hook, and the local governments will have to find $175.9 million for operations and maintenance.

The state will cover operating deficits for only seven years. Total local funding required out to 2036 is $764.3 million. Fare-box revenue would cover less than 20% of operating costs.

Plus, Sen. Dockery says because the A-line is vastly overvalued compared to its $22.2 million taxable value, the $641 million proposed deal with CSX is a rip-off for taxpayers. As it stands, CSX would get $416 million to make improvements to the S-line as compensation for moving freight capacity from the A to the S-line.

But, in fact, according to a letter to FTA Administrator James Simpson from FDOT District 5 Secretary Noranne Downs, the SunRail project does not require CSX to shift freight hauling from the A-line to the S-line. Downs' letter also states that CSX's “...plans for increasing capacity have been in place for some time and are not associated with the proposed implementation of commuter rail.”

Dockery believes she has enough allies in the Senate to kill the deal if big issues can't be resolved soon. She also has support from advocacy group Ax the Tax. Doug Guetzloe, chairman, recognizes the deal's inequities, saying, “CSX is getting paid way beyond anywhere else in the nation. This is a huge waste of taxpayer dollars.”

Tri-Rail, the 20-year old commuter rail line connecting Palm Beach County and Miami-Dade, had an $80.2 million operating loss in 2008. The $346 million Tri-Rail double tracking project completed in 2007 exceeded cost estimates by $14.5 million and ridership continues to lag its forecast.

SunRail is projected to carry 4,300 passenger trips per day when it's planned to open in 2011 and 7,400 a day by 2030 — modest numbers even if they are reached.

And, after voting to pursue high speed rail connecting Tampa, Orlando and Miami in 2000, Florida voters reversed course in 2004. (It's not dead, however — the Florida High Speed Rail Authority is looking to compete for a chunk of the $8 billion economic stimulus program for transit projects.)

Such experiences would seem to suggest alternatives. But Orlando Mayor Buddy Dyer, chairman of the Central Florida Commuter Rail Authority, speaks for seven counties and 86 cities supporting the plan, saying, “This is our number one priority.”

'Indemnify us'

Apparently, cost and liability issues are not the number one priority for Dyer. But Florida taxpayers could be tied to the track and staring at potentially huge liability exposure barreling at them.

CSX is demanding to be indemnified from any liability for damages to commuter trains or passengers in the case of an accident, even one caused by a CSX train using the line. At a March Transportation Committee meeting, Sen. Dockery told her colleagues, “We should ask CSX to indemnify us, not the other way around.” Nevertheless, the bill chugged ahead on a 6-3 vote.

Surprisingly, there is no exception for gross negligence or willful misconduct. A Feb. General Accounting Office (GAO) report instigated at the urging of U.S. Rep. Kathy Castor, D-Tampa, questions the wisdom of such liability agreements.

The provisions will now to be studied by the U.S. House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee.

On April 7, a Florida Senate committee agreed on new budget language that may allow the agreement to be finalized. Passing Senate Bill 1212 has already been a bumpy ride. It authorizes the liability insurance purchase requirements and the state's indemnification obligations set out in FDOT's tentative agreement with CSX.

That might be tough. Sen. Dockery has previously attempted 11 amendments in one committee stop and sits on the last committee to hear the bill. That meeting was set for April 15 — tax day.

No little plans

In Hillsborough County, rail plans are rolling from all directions. The Metropolitan Planning Organization's Transit Study estimates $6.2 billion in capital costs for light rail and commuter rail and $91 million in annual operating and maintenance costs.

HART, the county transit agency, supports a $68 million capital plan for bus rapid transit, and is pushing funding for light rail and commuter rail they would operate. Ed Crawford, HART's spokesman, is well aware of funding gaps, saying,

“The operating cost is really the big nut to crack, because transit systems don't make money.”

The county commission recently went against a TBARTA citizens' survey and initiated steps for a November 2010 sales tax referendum to raise up to $192 million for transportation improvements. The survey shows two-thirds of Hillsborough residents wanted the county to hold off on any proposals to increase taxes until TBARTA presents its plans to voters.

But $192 million is less than the annualized operation and maintenance costs estimated as high as $270-275 million. The capital costs for one TBARTA plan are in a wide range of $12-23 billion.

The preliminary 2050 version of the TBARTA plan calls for 242 miles of rail plus 449 miles of bus rapid transit and express bus service.

The seven-county group is set to adopt its plan in May and then will try to figure out funding sources, but only three — Hillsborough, Pinellas and Sarasota — can impose a transit sales tax.

Even if the state does not add a percentage point to the state sales tax, increasing taxes will be risky — the same TBARTA survey of Hillsborough citizens reveals the top two issues are high property taxes (12% of respondents) and taxation in general (10%). Traffic congestion came in third at 6%.

TBARTA is headed by Bob Clifford, who understands financial limitations will determine priorities. Even so, he offers, “What is the real objective here? It's to relieve congestion.”

The road less traveled

But other experts, like the Cato Institute's O'Toole, says that transit represents only 1.5% of all urban travel. New data from the Federal Highway Administration shows that the decline in vehicle-miles traveled is continuing and now exceeds 122 billion with Florida travel declining more than the national average and at a greater rate.

And O'Toole's research from the first quarter of 2008 shows that the increase in transit passenger miles is less than 3% of the decline in urban auto passenger miles. So, 97% of the decline is due to people carpooling, combining trips or just driving less — not taking transit.

According to O'Toole, “In 2006, urban transit agencies spent about $42 billion on 49.5 billion passenger miles, for a cost of 85 cents per passenger mile, or more than three times the cost of driving.” He adds, “Subsidies to public transit totaled about 61 cents per passenger mile, or 120 times the subsidies to autos and highways.”

As such, he maintains there are better options than heavily subsidized rail projects. He suggests improving highways and bus service, time of day toll road pricing, and traffic signal coordination, which by itself, “can save far more energy at a tiny fraction of the cost of building new rail transport lines.”

Rail transit advocates argue that the billions in expenditures are justified by energy concerns and the development generated around new stations. O'Toole says their concerns are misplaced noting that under federal laws autos are getting more energy efficient and that by 2035 the average auto will consume less BTUs per passenger mile than any urban transit mode today. And, he cites Portland, where the energy savings from operating a new light-rail line will take 172 years to pay for the energy cost of construction.

Regarding development around transit stations, O'Toole points to an FTA study showing that “urban rail transit investments rarely 'create' new growth, but more typically redistribute growth that would have taken place without the investment.” He adds that so-called transit-oriented development plans are popular with developers who get huge subsidies, and also because they're needed by government agencies involved to offset costs.

However, in the end, the strategy just creates congestion in order to supposedly relieve it.

There seems to be only one form of congestion guaranteed to be relieved— that of taxpayers' wallets.