- April 18, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Executive Summary

Company. Amscot Industry. Financial services, small-dollar lending Key. Company is fending off regulations it says could cripple its business.

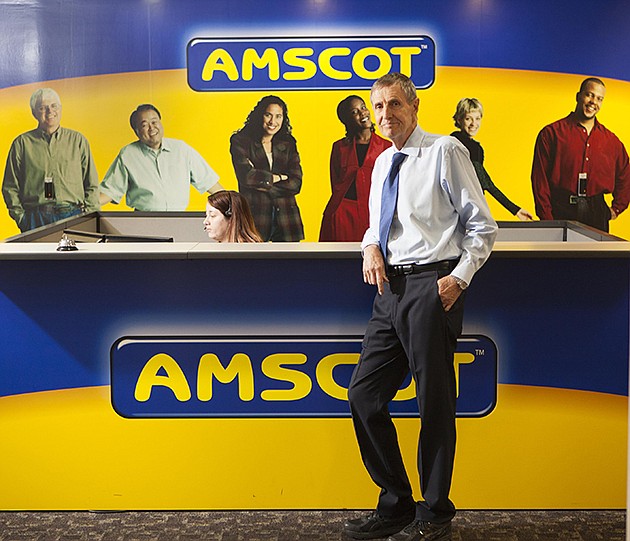

Ian MacKechnie's first business venture in the United States was a dismal — and costly — failure.

It was in 1988. Fresh of selling a chain of coffee and bakery shops he founded in his native Scotland for $18 million, MacKechnie had moved to Tampa for a new life challenge. Besides the weather, he chose the region because he had just finished reading John Naisbitt's bestselling book “Megatrends,” which named Tampa the fastest-growing city east of the Mississippi.

MacKechnie bought Lincoln Baking Co., which distributed fresh baked goods to 7-Eleven and Circle K convenience stores. But he struggled to get enough volume.

Rather than invest more money in it, he sold the business, at a $1 million loss.

MacKechnie rebounded quickly. In 1989, he founded Amscot Financial. He saw a need for a low-cost alternative for people who cashed checks at liquor stores and pawnshops, in what was then a largely unregulated field. What began as two check-cashing stores, one in Ybor City and another near the University of South Florida, has turned into a statewide leader in small-dollar, quick-serve financial services.

The company handles $7.5 billion in transactions a year, with a list of services that include cash advances, bill payments and free money orders. It does that through nearly 240 locations the company operates statewide, with the bulk in the Tampa, Orlando and Miami-Dade-Broward markets. All the stores are open from at least 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., and one-third are open 24 hours, to cater to its mostly working-class customers.

“We are successful because we do what our customers want us to do,” says MacKechnie, a spry 72-year-old who uses a treadmill desk at work to stay active. “We don't work bankers hours. We are open 365 days a year. There is a demand for this.”

Amscot had $209.3 million in revenue last year and has 1,800 employees. The payroll includes about 150 people in its Tampa headquarters, where it occupies two floors of an office tower in Tampa's Westshore district with its name on top. The company also has a 30,000-square-foot ground facility nearby, where it houses IT services for its branches, equipment and a printing facility for marketing materials. MacKechnie is chairman and CEO of the company. His two sons, Ian A. MacKechnie, 48, and Fraser MacKechnie, 41, are top executives.

More caps

Now, after 27 years, Amscot faces what could be its biggest challenge ever — pending federal regulations from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau that would most likely put the company out of business, or at a minimum, cripple its business model.

Ian A. MacKechnie, an executive vice president and treasurer at Amscot, says the rules as written are a death penalty. It would turn the company's niche quick transactions into the equivalent of signing a 30-year mortgage, he says.

“These rules are really onerous and complicated,” he says. “It isn't regulation, it's prohibition.”

The Florida Office of Financial Regulation oversees all licensed payday loan business in the state. The OFR caps fees lenders can charge customers at $10 per $100 borrowed over 31 days. The state also caps the total amount a customer can loan at one time at $500. Borrowers are required to be compliant with a state database that red-flags customers with checkered payment histories, and lenders are required to use the database with every transaction. And customers who don't repay a loan are given a two-month grace period, and financial counseling.

But a segment of the proposed CFPB rules would put even more restrictions and caps on loans, both to thwart what it calls predatory lenders and essentially protect customers from themselves. CFPB Director Richard Cordray, in public comments on the rules, says the sheer economics of the payday loan industry require some borrowers to default. Then those customers come back for more loans, fall behind and quickly fall into a downward debt spiral.

“These rules would rein in the most abusive of the payday lenders,” says Karl Frisch, executive director of Allied Progress, a Washington, D.C.-based lobbying group that supports the rules. Frisch, in an interview with the Business Observer, adds he hopes the CFPB doesn't relent and water down the rules, so companies can find loopholes.

The public comment period for the proposed rules ended Oct. 7. The CFBP, created in 2011 from the Dodd-Frank financial industry reform act, is expected to announce the official rules sometime in 2017.

MacKechnie says Amscot isn't “going to sit back and do nothing,” about the proposed rules, including potential legal action. The Community Financial Services Association of America, a leading industry lobbying group, also could take action.

'Fill the void'

MacKechnie has found himself on the wrong side of regulators once before in his 50-year business career.

It happened about a decade after he launched Amscot, when he started to offer auto insurance to high-risk motorists. MacKechnie was charged with insurance fraud and conspiracy to commit racketeering following a sting operation from then Florida Insurance Commissioner Bill Nelson's office in 1998.

Charges in the case were ultimately dropped, and MacKechnie agreed never to return to the insurance industry. But MacKechnie says the experience, and the legal fees, made him overzealous when it comes to following regulations.

That's partially why Amscot has 20 people on the corporate payroll who handle compliance with Florida's stringent payday lending regulations. That includes 10 retired FBI agents who do forensic accounting in all the chain's stores.

“If we go away,” asks MacKechnie, “will the people who fill the void be as diligent?”

Like many executives in financial services, including banks and credit unions, MacKechnie says he welcomes regulation. “Any good business supports good, well-intentioned, fair regulations,” he says. “We don't want bad operators in our industry.”

MacKechnie concedes, too, that it doesn't hurt that stiff regulations create a sizable barrier to entry for competitors. Says MacKechnie: “It's enlightened self-interest.”

The other barrier to entry, and challenge for Amscot, is capital. It takes significant startup and ongoing capital to reach $7.5 billion a year in transactions, say company officials.

Amscot, says MacKechnie, has received $80 million to $100 million in institutional investor money during the past decade to fund loans and business operations. On the

operations side, he says it costs at least $1 million to open a branch. That covers training, security and build out of the locations, which are leased. The company also spends a significant amount on advertising, especially when it enters a new market.

“The margins are relatively small,” MacKechnie says, “so we understood the need for critical mass.”

Lots of letters

That critical mass of customers is now Amscot's best weapon against the proposed rules.

For starters, MacKechnie says the default ratio of Amscot's customers is around 1%, which renders the CFPB's claims of a payday loan debt trap mostly false.

Then there are the letters.

Amscot, through clerks and managers at branches, asked customers to write letters about their experience with the company it could use for the comment period of the proposed CFPB rules. The response was a deluge of hand-written letters and notes, 103,000 in all, that rave about Amscot. Copies of the letters are stacked in piles on top of a large table in a conference room in Amscot's headquarters.

Most of the letters share a theme: Amscot provided a loan that allowed customers to turn on the power or buy groceries for a week or get medicine for a family member. The notes, to MacKechnie, are proof positive he's in the right business, and Amscot does right by customers. “We want to be something people want in their community,” he says. “We don't want to be a nasty payday loan place.”

MacKechnie also says the proposed CFPB rules go against a core American value: freedom. “I came to this country 30 years ago because I thought it was the last bastion of capitalism,” says MacKechnie. “The Constitution clearly states this is a free-market economy.”

Survival stories

Here are examples of comments Amscot customers wrote about the company in response to proposed federal regulations that would cripple the business. (Last names weren't provided for privacy.)

“If you limit loans you are going to cause many families to be homeless, foodless, without running water or heat and air conditioning.”

Janie, Riverview

“I'm disabled so I receive a small amount of disability a month. This really helps me survive through the month.”

Tania, Palmetto

“I am a single mom who works two jobs, unfortunately it's not enough. Cash advances allow me to get what I need done when I come up short.”

Amber, Sarasota

“If the water heater breaks or the family car is not working what will we do? Families need these services so any limits imposed will destroy the fabrics of the family household. We should have the right to choose.”

Derron, North Port.

“Payday Advances have been a tremendous help to our family in times of need. If we have to wait 30 days or even limiting us on how many a year, we would be in a bad spot.”

Catherine, Palmetto

Big pay

A breakdown of the $7.5 billion that passes through Amscot every year includes:

$2 billion in money orders;

$1.5 billion in loans of $100 to $500 each;

$1 billion in bill payments;

$1 billion in check cashing.