- November 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

About 1,800 Hillsborough County School District teachers quit their jobs last year. To date, with the school year under way, the district has 566 instructional job openings. That's up from 181 teacher openings this time last year, an increase of 212.7%

While jarring, those numbers are bigger, in part due to the district's size. With nearly 25,000 employees and at least 215,000 students, Hillsborough is the third-largest school district in Florida and among the top 10 of all school districts nationwide.

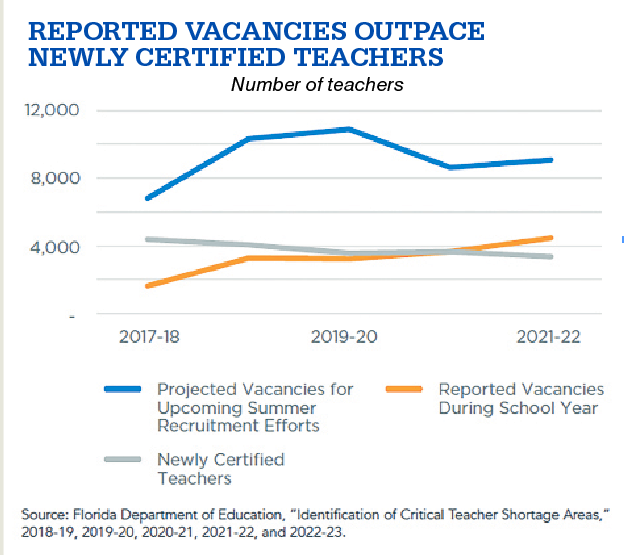

Smaller districts in the region are also in the market to hire more teachers, fast. When the school year started in mid-August, Collier County had 50 open spots for teachers; Polk had 286; Sarasota had 82; Pinellas had 172; and Lee County had 194. For deeper context, Lee, with some 6,000 teachers overall, had 84 unfilled teacher positions at this time last year. That's a 131% increase in vacancies in one year — enough to drive any business leader and hiring manager batty, just like Hillsborough.

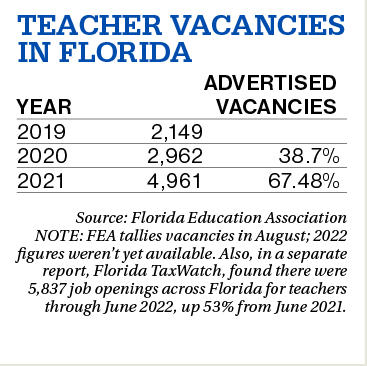

And that's just a sampling of the situation: According to an August 2022 report by Florida TaxWatch, there were 5,837 job openings statewide for teachers as of June 2022. That’s a 53% increase from June last year. More startling? On a national scale, more than half, 55% of full- and part-time teachers say plan to leave the profession, according to a National Education Association report.

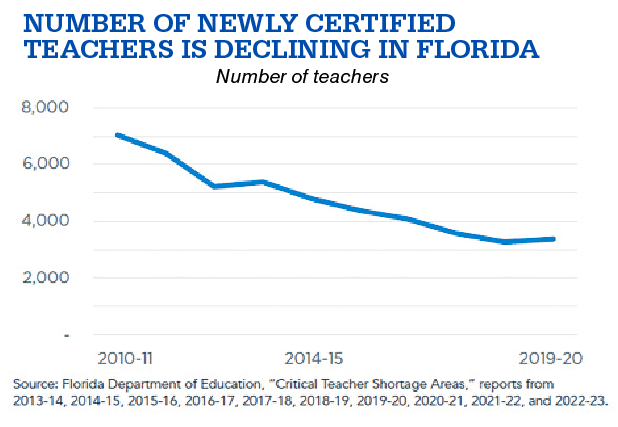

“It is a huge number,” says R. Anthony Rolle, dean of the University of South Florida College of Education. Rolle was appointed to lead the 2,200-student institution in June 2021 — in the wake of a turbulent time at USF that featured a proposal, since withdrawn, to dismantle the College of Education because of sluggish enrollment — and has identified several reasons why teaching is in decline as a profession.

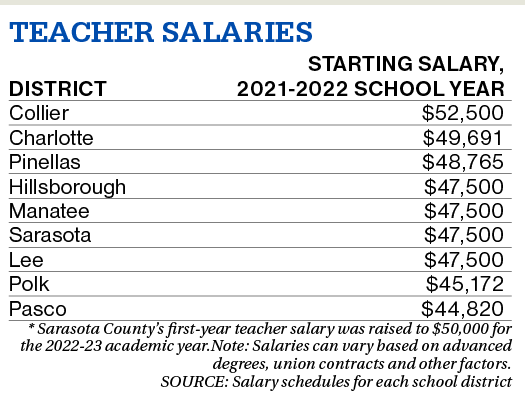

“In Florida, the starting salary is about $47,500, but nationally, the average salary for college graduates is over $55,000,” he says. “So that’s one set of issues. Also, there’s a general sociopolitical sense that teaching no longer is valued as a profession, no longer valued with respect, along with a general belief, somewhat reinforced through COVID experiences, that anyone can teach a child.”

The challenges facing K-12 schools are massive and should worry, if not outright alarm, the business community. An educated workforce, fed by a robust supply of good schools, is an essential ingredient for economic development. The teacher shortage crisis could derail much of the progress Gulf Coast cities have made in terms of recruiting companies to the region. It could even cause homegrown entrepreneurs to pull up stakes and depart for states that better prioritize education.

“One of the first concerns that a new business or relocating business has is your education system,” Rolle says. “So, in order to build a baseline for economic development, we need to maintain and enhance the strength of the schools that we have, while developing the schools we need for the future in terms of academic, economic and social justice opportunities for both our community and the businesses who want to relocate here.”

Noble goals. But how can Florida schools turn the tide of teacher burnout and dissatisfaction?

An obvious answer starts with where many business go to first: salaries. While it’s true that, thanks to an allocation of $800 million in state funds, the starting salary for new teachers has risen — at about $47,500, it’s now the ninth-highest in the country, according to the National Center of Education Statistics — the average Florida teacher salary, $49,583, is the second-lowest in the nation.

Moreover, when adjusted for inflation, Florida’s average annual salary for K-12 teachers has declined, by 13%, since the 2009-10 school year.

Chad Leibundguth, Tampa district director at Robert Half, a recruiting and staffing firm with offices nationwide, says the teacher shortage crisis “has a little bit of uniqueness to it because of some of the challenges with compensation.” Low pay, he adds, “is a biggie … in whatever sector you’re hiring in, you need to make sure you’re providing a compensation range and package that is commensurate with the market and what you’re looking for. I think that’s probably a big driver of what’s happening with the teacher market.”

Money is an important thing, but it's not the only thing.

The pandemic, Leibundguth says, also gave rise to a host of other factors that lured teachers away from the education sector. The post-pandemic labor market, for one, created new opportunities for teachers, who possess in-demand leadership and communication skills easily transferrable to other industries.

Teachers, Leibundguth says, “clearly know how to work with people, deal with difficult situations and problem solve. I think the variable, candidate to candidate, might be technology. That’s a big, important driver. ‘Are you tech savvy? Can you learn our software?’ If you’re a teacher who’s kept up to speed from a software perspective, and you’re tech savvy, that’s going to open a lot of doors in many industries.”

The observations of Gary Meyer, CFO and interim CEO of the Early Learning Coalition of Hillsborough County, align with Leibundguth’s assertions. Teachers leaving the profession entirely is the biggest threat he’s seen to education, he says, but his organization is taking steps to make life easier for educators.

“We have a host of things we are doing to combat the wave of teachers leaving for something else,” Meyer says. That includes wellness and mindfulness training sessions and what he calls anti-burnout sessions. “Those were wildly popular.”

Meyer’s organization, which provides resources and information for early childhood care and education programs, has seen some incremental progress in staffing levels of Tampa area early education providers. In July, its job board listed 40 openings for Hillsborough early learning entities— a number that has since declined to 18, he says. That stems mostly from a $4.1 million grant for pay raises and support, including funding for more teacher aides. “The funding at the federal and state level has increased dramatically, and that has really helped us address this issue,” Meyer says.

Unfortunately, for schools and organizations short on resources, a vicious cycle can arise. Staff shortages lead to larger class sizes and greater workloads for teachers, which creates an unfavorable environment for retention. That was a big takeaway the NEA found in its survey, released in February, that found 55% of teachers are ready to move on from the profession much sooner than previously planned.

“After persevering through the hardest school years in memory, America’s educators are exhausted and increasingly burned out,” National Education Association President Becky Pringle says in a statement that accompanied the survey results. “School staffing shortages are not new, but what we are seeing now is an unprecedented staffing crisis across every job category."

At the local level, educators such as Amanda Jae, day school director at Palma Ceia United Methodist Church and Day School in South Tampa, are addressing teacher burnout with renewed vigor. Like Meyer, Jae is also part of the Early Learning Coalition of Hillsborough County, sitting on the board. She says financial compensation is just one piece of the teacher retention puzzle. More perks and benefits in line with other professions, such as additional paid time off and professional development opportunities, are key.

“It’s my job to support and help teachers, help alleviate the pressure so they can go in the room and be Mary Poppins,” says Jae, who has implemented raises and more PTO for her school’s teachers, in addition to reducing class sizes. “It’s a really stressful job, and if you don’t work for a [school] that supports you, why would you want to continue to work there?”

To better support teachers and staff, though, schools need better financial support, and local taxpayers, reeling from inflation, don’t always seem to be in the mood to provide that. In Hillsborough County, for example, a millage tax referendum on the August primary election ballot would have raised enough money to increase teacher salaries by $4,000 per year. The measure failed to pass, though by the narrowest of margins — a mere 590 votes, triggering a recount that confirmed the result.

Hillsborough school officials are pragmatic about the rejection. (Several other counties in the region have passed similar measures in recent years including Charlotte, Collier, Lee, Manatee and Sarasota.) And even before the referendum, the district was proactive, spending $26 million to boost teacher pay, in addition to using federal stimulus funds for $2,000 bonuses for special education teachers.

“We had, of course, hoped for the millage proposal to pass [so] we could provide a more substantial pay increase to teachers to fill the gaps in funding received from the state,” says Erin Maloney, a spokeswoman for Hillsborough County School District, in an email response to questions from the Business Observer. “However, now that the recount has completed, we must continue our financial recovery plan, which includes ensuring staffing allocations remain consistent with funding we receive from the state.”

Maloney says that plan, implemented by Superintendent Addison Davis in 2020, “has brought our district from a $100 million plus deficit to a $2 million surplus. This is the first surplus we have realized in a decade. Without the additional funding from the millage, the recovery will be slower. However, Superintendent Davis looks forward to returning in 2024 to our community to recommend the millage initiative once again.”

Maloney says school leaders have been proactive in addressing the crisis, citing job fairs and increased engagement with area colleges and universities to foster the recruitment of new educators to the district. Multiple districts are getting into the job fair game, including Sarasota and Manatee.

“This shortage is not unique to Hillsborough County Schools,” she says, “but our goal is to put highly qualified teachers and support staff in every open position that we can.”

In the meantime, Maloney says, Hillsborough schools have gotten creative with staffing. “We deployed approximately 300 district-level employees with teaching certificates into classrooms that were without a full-time teacher,” she says. “We will look at moving teachers to areas where they are needed most while adjusting teacher and student ratios when needed.”

Somewhat related, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has proposed a measure that would bolster the state’s teaching ranks by bringing retired first responders, police officers and military personnel, even those who don’t have bachelor’s degrees, into classrooms as teachers. The idea was met with intense criticism, including from Democrats and teachers unions.

Rolle, the USF education dean leading an effort to train more teachers, doesn’t outright dismiss DeSantis’s idea to solve the shortage. But he worries about a decline in the state’s quality of K-12 instruction if less-than-qualified teachers are rushed into schools.

“I’m not saying that military and first responders cannot be good teachers,” he says. “What I’m asserting is that most of these individuals cannot leave one position and go directly into the teaching field without additional knowledge, skills, abilities and preparation. I’m proud to be the son of a military family — my uncles all work in the armed services, and I do believe that any of those individuals could be great teachers, but only with appropriate levels of knowledge, skills and abilities.”

Also, Rolle points out, the governor's proposal is not wholly original. The U.S. Department of Defense already has a Troops to Teachers program that aims to assist active and retired members of the military become certified as K-12 teachers and employed by schools. TTT was reauthorized in December 2021 and funding levels have yet to be determined, but Rolle says he and his colleagues are looking into how the USF College of Education can take advantage of the program.

"As we sit here in South Florida," he says, "with the expertise at the military bases around us, we can provide opportunities for military personnel to become excellent teachers, in time."

Rolle acknowledges the fiscal realities of public education are complex thanks to a three-tiered government funding system — federal, state and local — but ultimately, he says, it falls upon Tallahassee to make Florida a more attractive employer for teachers. Instead of turning to veterans to solve the teacher shortage crisis, state leaders should take a much simpler approach.

“Typically, if there’s a shortage in a high-need area — and this is basic economics — what you do is acknowledge that supply is low, and you increase salary,” Rolle says. “As salaries increase, more people enter the market, and more high-quality people enter the market who are trained.”

Mark Gordon and Amanda Postma contributed reporting to this story.